In 1982, artist Agnes Denes created a powerful statement by planting 2.2 acres of wheat on vacant land in New York's Battery Park, with the World Trade Center towers looming overhead. Her work, Wheatfield: A Confrontation, highlighted what she termed a "powerful paradox" - the existence of hunger in an increasingly wealthy world.

The Growing Challenge of Global Food Security

When Denes created her installation, the global population stood at 4.6 billion. By 2050, projections indicate this number will more than double, raising serious concerns about our ability to feed everyone. Currently, food insecurity affects 2.3 billion people worldwide, with recent crises including the COVID-19 pandemic and extreme weather events exposing critical vulnerabilities in our global food systems.

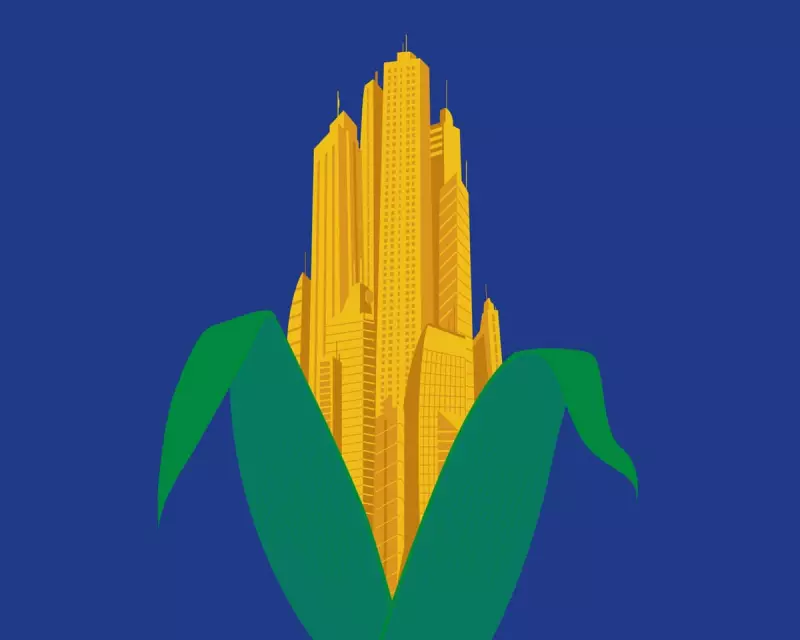

Denes's work appears increasingly prophetic as we look toward future solutions. With more than two-thirds of humanity expected to live in urban areas by 2050, the question becomes urgent: Could urban farming help feed 10 billion people?

What Exactly is Urban Agriculture?

Urban agriculture encompasses a diverse range of practices, from high-tech solutions like vertical farming and soil-free methods including hydroponics, aeroponics and aquaponics, to community gardening on unused urban land. The concept isn't new - victory gardens supplemented food supplies during both world wars, while the 1970s and 80s saw the "green guerrilla" movement transform hundreds of vacant Manhattan lots into productive spaces.

The United Nations recognised urban agriculture's developmental importance in the 1990s, and during the Syrian civil war, citizens of besieged eastern Ghouta demonstrated remarkable resilience by farming mushrooms in their basements.

The recent pandemic sparked a significant urban farming boom, with £4.5 billion invested in vertical farming startups during 2021 alone. Although many ventures struggled as lockdowns eased, the concept continues to demonstrate remarkable resilience. In January, the Scottish government inaugurated a new £1.8 million Vertical Farming Innovation Centre, while innovative farms have emerged in diverse locations including Brooklyn shipping containers, Parisian underground car parks, second world war bomb shelters beneath London, and rooftops across Hong Kong and Singapore.

The Multiple Benefits of Urban Farming

Currently, urban agriculture produces between 5% and 10% of the world's legumes, vegetables and tubers. Expanding urban farming could significantly improve diets in developed nations while providing essential calories for the Global South. A 2025 study suggests urban agriculture could contribute significantly to meeting the UN's 2030 sustainable development goals addressing hunger, sustainable cities and responsible consumption.

The environmental advantages are substantial. A 2013 study found that food grown in London produced 2.23kg less CO2 per kilogram compared to conventional agriculture, primarily by reducing transportation and packaging requirements. Soil-free growing methods ease pressure on agricultural land and waterways, with the World Economic Forum estimating that vertical farming uses up to 98% less water than traditional farming.

Additional benefits include rainwater harvesting from rooftops, recycling urban wastewater, and reducing the urban heat island effect through green roofs. Perhaps most importantly, urban farming promotes food sovereignty, empowering communities and enriching individuals by reconnecting them with food production.

Challenges and Realistic Solutions

Urban agriculture isn't a perfect solution. Open-air farming near roads risks introducing pollutants into the food chain, while indoor vertical farming remains highly energy-intensive. A single vertical farm occupying a 30-storey building with a 5-acre footprint could produce yields equivalent to 2,400 acres of traditional farmland, operating year-round regardless of climate conditions. However, scaling this approach to planetary levels would require unsustainable energy inputs.

The most practical approach involves a patchwork strategy matching methods to local conditions. Energy-intensive hydroponic farms suit regions like the Gulf states, where 85% of food is imported and abundant renewable energy is available. Elsewhere, lower-impact farming on urban fringes, while less productive, represents a more sustainable option.

Agroecology - a holistic approach defined by principles including environmental responsiveness, soil health, biodiversity protection and minimising external inputs - offers particular promise. This method could transform street corners and waste grounds into productive spaces while addressing what researchers call "nature connectedness", which has declined by 60% since 1800.

Local Success: Edinburgh's Lauriston Farm

In Edinburgh, just a mile from the city centre, Lauriston Farm demonstrates agroecology in practice. This cooperative is converting 100 acres of former sheep pasture into a dynamic mix of market garden, community allotments, agroforestry, orchards, and restored wetland and meadow. Like Denes's Wheatfield, crops grow within sight of residential towers, creating one of the city's most quietly radical spaces.

While Lauriston Farm alone cannot feed Edinburgh, it exemplifies how small-scale initiatives collectively achieve significant impact. Globally, small farmers produce between one-third and one-half of the world's calories without resorting to damaging industrial agricultural practices.

Urban agriculture alone cannot feed 10 billion people, but neither can we afford to ignore its potential. Success requires addressing multiple challenges simultaneously: preventing food waste, preserving soils, halting pollution, arresting climate breakdown and protecting biodiversity, especially pollinators. As filmmaker Derek Jarman wrote, "My garden's boundaries are the horizon." Every change, however small, expands our understanding of what's possible.