The haunting image of a North Atlantic right whale navigating Massachusetts Bay with her calf reveals a stark contrast between natural rhythms and human demands. As these endangered mammals follow ancient migratory patterns, container ships plough through their habitat on fixed schedules dictated by global commerce.

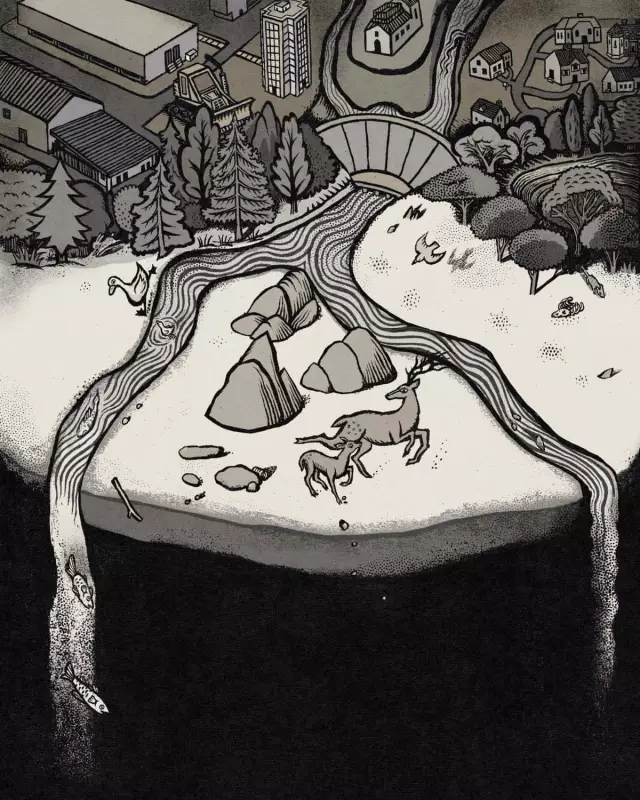

This collision of worlds represents more than just an environmental concern—it exposes a deep-seated philosophical belief that underpins our relationship with the natural world: human exceptionalism.

The Psychology of Separation

Human exceptionalism operates as the conviction that humans aren't merely different from other life forms, but morally superior to them. This belief grants us perceived entitlement to priority access to space, resources, and survival at the expense of other species.

Psychologist Erik Erikson identified this tendency as pseudospeciation—the human inclination to divide the world into "us" and "not us" to justify mistreatment. This psychological distancing allows us to degrade beings we consider inferior without troubling our conscience.

The consequences are devastatingly tangible. For the North Atlantic right whale, already reduced to just a few hundred individuals, every threat they face—from ship strikes to fishing gear entanglement—stems from this root assumption that human needs matter more.

Indigenous Alternatives and Scientific Reality

Many cultures have long modelled a different relationship with nature. The Māori concept of whakapapa recognises kinship with rivers, mountains and forests, captured in the saying "I am the river and the river is me." Similarly, Lakota philosophy expresses Mitákuye Oyás'iŋ—"all are related"—framing animals, plants and natural elements as relatives rather than resources.

Modern science increasingly supports these ancient worldviews. Our 98.8% DNA similarity with chimpanzees and 98.7% with bonobos underscores our biological connection to other animals. Primatologist Frans de Waal termed the refusal to acknowledge this anthropodenial—a blindness to humanlike traits in other animals and animal-like traits in ourselves.

Charles Darwin argued in The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals that human feelings represent evolutionary continuities shared with other species, though this perspective was later suppressed by 20th-century behaviourism.

Legal Recognition and Practical Solutions

Despite political resistance, the rights of nature movement is gaining ground globally. New Zealand's Whanganui River, Colombia's Atrato River, and Spain's Mar Menor Lagoon now hold legal personhood status, while Canada's Magpie River has achieved similar standing through Indigenous resolutions.

Environmental writer Ben Goldfarb notes that while these developments represent progress, the concept of decentering humans remains "political anathema" in many quarters. He points to Utah legislators who passed a law specifically preventing personhood from being granted to any plant, animal or ecosystem.

Yet practical solutions demonstrate that coexistence is possible. The Wallis Annenberg wildlife crossing over Los Angeles's US Route 101 and Utah's Parleys Canyon overpass have significantly reduced wildlife-vehicle collisions, proving that strategic compassion works.

Individual actions also contribute to change: planting native species, reducing pesticide use, supporting wildlife corridors, and adopting more plant-based diets all help broaden our circle of consideration.

As biologist EO Wilson observed, humanity's central challenge lies in our "Paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions, and godlike technology." The whale asks for more space, the river asks for standing, and the tern asks for habitat. Our survival may depend on learning to listen.