While many families welcome the New Year with champagne and resolutions, one clan in Western Australia marks the occasion with a decades-long tradition of aquatic warfare. For the Shea family of Fremantle, New Year's Eve is synonymous with an epic, intergenerational water bomb battle that has raged for close to half a century.

The Origins of the Floodbath

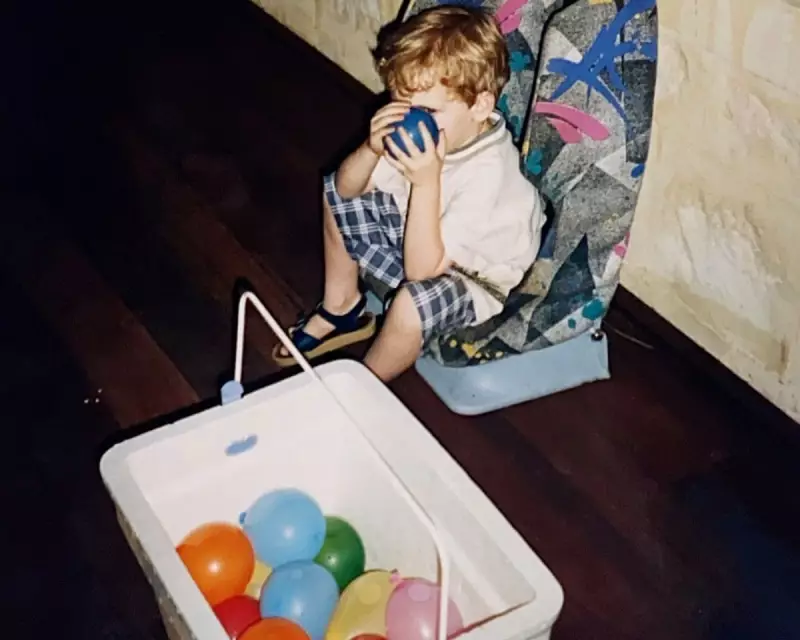

The tradition began in 1977 when Patrick Marlborough's parents started hosting a massive New Year's Eve party. The event, attended by an extended family boasting 115 cousins plus friends, features the usual hallmarks of a celebration: abundant food, a legendary esky known as "the mushroom," and raucous singing. However, it is distinguished by the organised chaos of a water balloon fight that involves participants aged from two to 90 years old.

The scale of the operation is immense. In the lead-up, family clans prepare by filling hundreds upon hundreds of water balloons, storing them in bin bags and car boots. As the party progresses in the backyard, an "engineering corps" works tirelessly at outdoor taps and the cellar sink to maintain a communal stockpile. The tension builds until groups naturally peel off to line opposite sides of the street, using parked cars as bunkers.

Rules of Engagement and Raids on the Town

The street battle operates with its own peculiar etiquette. Elders act as umpires from the veranda, vigilantly watching for traffic and innocent bystanders. The heart of the defence is the family's giant white van, a mobile citadel that also served a more offensive purpose for about 30 years.

This was the launchpad for the notorious "bombing raids" on Fremantle itself. With the matriarch at the wheel and up to a dozen cousins crammed inside, the van would descend into town to target New Year's revellers. Strict rules governed these assaults: no direct hits on people (aim for feet or walls), and absolute bans on targeting the homeless, pregnant women, people with disabilities, or police officers.

"Nothing felt as good as bursting a balloon on a sloshed goofball's boat shoes before zooming away yelling 'Happy new year!'" recalls Marlborough. The raids became a local fixture, sometimes continuing until 2am, and even attracting retaliation from the Fremantle fire station crew, who would lie in wait with a hose to drench the passing van.

The Tradition Winds Down

The external raids ceased in the early 2000s after a confrontation with police, who threatened to arrest two pregnant cousins. Subsequently, the warfare turned inwards, with the street battles growing even more ferocious. Over generations, tactics evolved to include water pistols and filling devices, but the core ritual remained.

Yet, all traditions eventually fade. The author notes that the street war has now largely ended. Younger family members are too preoccupied with their phones to risk a soaking, and adults in their mid-30s harbour more qualms about soaking toddlers than their predecessors did. The morning-after clean-up, involving collecting thousands of balloon shreds in the 35C heat, also gives pause for reflection.

Despite the environmental impact and the passage of time, the family feels no real remorse. Nostalgic conversations have even sparked talk of a revival. So, for anyone in modern Fremantle who might suddenly find their feet soaked by a well-aimed balloon from a speeding white van, know it comes with a heartfelt, if damp, "Happy New Year!"