The independence of British courts and public trust in the legal system face significant threats from Justice Secretary David Lammy's controversial proposals to dramatically reduce jury trials, according to legal experts and political commentators.

The Backlog Crisis Demanding Action

Britain's court system is undeniably in crisis, with victims of crime being told they might wait until 2029 for their cases to be heard. This unbearable delay forces traumatised individuals to either endure years of uncertainty or abandon their pursuit of justice altogether. Defendants similarly face lives put on hold, with witness memories fading over time.

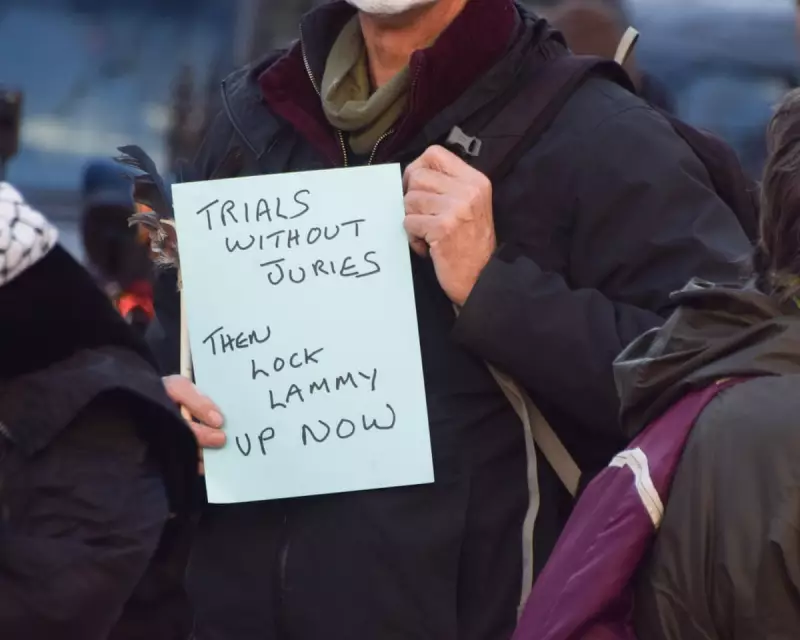

Something clearly must change in a system described as fundamentally broken. However, the solution proposed in a leaked letter from Justice Secretary David Lammy - scrapping jury trials for all but the most serious cases involving rape, murder, and offences carrying sentences longer than five years - has raised serious concerns among legal professionals and civil liberties advocates.

Why Juries Remain Essential Despite Flaws

Anyone familiar with courtrooms knows that real juries rarely resemble the idealised versions seen in legal dramas. Ordinary citizens tasked with dispensing justice bring all their human imperfections - they can become distracted, bored, or occasionally focus on irrelevant details like a witness's appearance.

Juries face legitimate criticism for being notoriously reluctant to convict in complex rape cases, and expert doubts raised over the Lucy Letby murder conviction have strengthened arguments for removing juries from cases involving highly complex medical evidence.

Yet despite these shortcomings, juries remain absolutely vital to justice being seen to be done. As Lady Helena Kennedy KC noted, public confidence in institutions depends on public involvement in processes that might otherwise appear remote and inaccessible.

The Hidden Dangers of Lammy's Proposal

Jury service represents the only opportunity most citizens have to witness the legal system in action. Excluding the public from this process seems unlikely to build greater confidence in the courts.

For defendants and their families, the right to be judged by one's peers - including people who may more closely resemble the person in the dock than the judge in the wig - carries profound significance. Even with an increasingly diverse judiciary, juries are widely seen as a crucial safeguard against institutional racism.

As David Lammy himself argued before becoming Justice Secretary, twelve people with competing biases may collectively cancel out each other's assumptions more effectively than a single judge, however well-trained in impartiality.

Perhaps most concerning in the current political climate, juries represent a vital protection against the politicisation of courts. Judges are appointed through processes that could potentially be influenced by future governments with questionable intentions, unlike juries selected randomly from electoral registers.

The Real Causes of Court Gridlock

The fundamental question remains whether targeting juries addresses the actual causes of court delays. When only 1% of criminal cases in England and Wales actually reach a jury, this proposal seems more like a distraction from the real issue: chronic underfunding of the justice system.

The judicial backlog represents the legacy of previous governments' spending choices, similar to NHS waiting lists and the asylum seeker hotel crisis. The system has deteriorated due to inadequate funding not just for courts, but for essential supporting services.

Lengthy delays in analysing mobile phone data, obtaining reports from probation officers and social workers before sentencing, and time wasted by defendants ineligible for legal aid attempting to use ChatGPT for their own defence all contribute significantly to delays.

Meanwhile, the growing complexity of legislation - often resulting from Parliament responding to public demands for action - and more proactive policing of complex historical sexual abuse cases means police and prosecutors are doing exactly what society asks, but without adequate resources.

The Leveson Review Context

Lammy's proposals follow a review by Sir Brian Leveson KC that suggested removing defendants' right to request jury trials in some "either way" cases, creating a new juryless division of judges and magistrates, and permitting single judges to hear serious cases when defendants choose this option or case complexity warrants it.

Critically, Leveson's terms of reference required him to consider the "likely operational and financial context" - essentially acknowledging the severe budget constraints facing the justice system. While scrapping jury trials wouldn't save substantial money directly, Leveson calculates it would free up 20% of court sitting time, allowing more cases to be heard within existing budgets.

This approach mirrors the gamble underlying Rachel Reeves's budget - the hope that something will turn up before 2029, avoiding more difficult choices, with all the associated risks and potential rewards.

As the legal maxim states, justice delayed is justice denied. The concern now is whether justice on the cheap might become justice discredited, with lasting consequences for Britain's legal system and democracy.