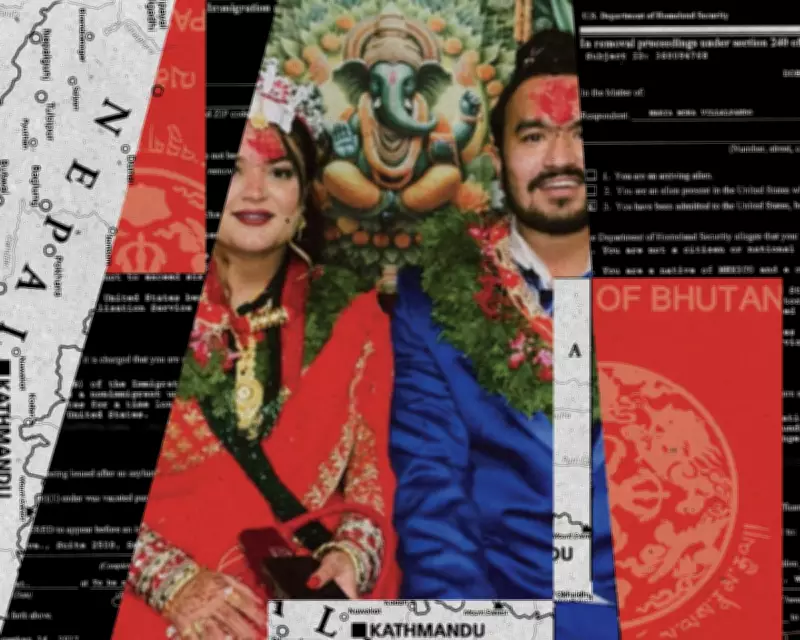

Stateless Father Deported to Bhutan by ICE, Separated from Wife and Infant Daughter

Mohan Karki, a 30-year-old man who has never held his seven-month-old daughter, was deported to Bhutan on January 13th after more than nine months in immigration detention. His removal came despite a series of legal battles led by his wife and attorneys who fought to stop what they describe as a dangerous deportation to a country where Karki has no legal status, family connections, or language proficiency.

A Family Torn Apart

Tika Basnet, Karki's wife, now raises their infant daughter Briana alone in Ohio while her husband lives in hiding somewhere in South Asia. During a recent video call, Basnet sat with their sleeping daughter on her lap as Karki's pixelated face appeared on her iPhone screen from nearly 9,000 miles away.

"I feel like a ghost," Karki said in Nepali during the call. "Living in the shadows. No home, no name, not even an identity card that says I belong anywhere."

Karki's deportation represents what human rights advocates describe as a troubling pattern under the current administration, which has increasingly removed people—including refugees—to countries with which they have little or no connection, often placing their lives in danger.

A History of Statelessness

Karki's story begins with a history of displacement that spans generations. He was born in a refugee camp in Nepal after his parents were among more than 100,000 ethnic Nepali-speaking Bhutanese forced out of Bhutan during a state-led campaign in the early 1990s that stripped them of citizenship and property.

"What we are seeing now in the United States is not new for many Nepali-speaking Bhutanese," said Robin Gurung, co-executive director of Asian Refugees United. "Back then, the government decided who was worthy of citizenship based solely on ethnicity."

Both Karki's and Basnet's families eventually resettled in refugee camps in eastern Nepal, where tens of thousands of displaced Bhutanese lived for decades. "Life in the camp was depressing," Karki recalled. "We didn't have enough food. We didn't feel safe."

American Dreams Unraveled

In early 2008, under the George W. Bush administration, the United States began a large-scale resettlement program for Bhutanese refugees. By the end of Barack Obama's second term, more than 85,000 Bhutanese refugees had been resettled in the U.S., including both Karki's and Basnet's families.

Karki's family arrived in Georgia in 2011, the same year Basnet's family resettled in Ohio. "What I liked about Georgia, about America, was the abundance," Karki said. "I convinced my father that once I finished high school, I wanted to join the U.S. army, to give back to this country."

That dream unraveled in February 2013 when Karki, then 17, and two friends were arrested in Georgia and charged with burglary, criminal trespassing, and interference with government property. Karki has disputed the intent behind the incident, saying they were simply trying to get home quickly after school by jumping a fence as a shortcut.

According to court transcripts, prosecutors alleged that jewelry was taken from the residence, though the case never went to trial and no witness testified to seeing a burglary or theft. Karki accepted a plea deal after his lawyer told him he could go home that day if he agreed, versus potentially staying in prison for 25 years if he didn't.

The Brutal Mechanics of Immigration Law

Brian Hoffman, Karki's immigration attorney, explained how cases like this reveal systemic failures at the intersection of criminal and immigration law. "If your own lawyer is telling you, 'This is a good deal, you should plead guilty,' you're not really listening to warnings about immigration consequences," Hoffman said.

He added that crimes that may be minor under state law can be reclassified as "aggravated felonies" for immigration purposes, triggering mandatory detention and deportation. "It doesn't make any objective sense," Hoffman said. "But that's the system."

In August 2014, an immigration judge ordered Karki's removal from the U.S. He was detained for about a month, then released under supervision after neither Bhutan nor Nepal accepted him. For years, Karki maintained regular ICE check-ins, earned his GED, and worked at a meat-processing plant in Georgia.

Building a Life Together

In 2021, while visiting family near Columbus, Karki met Basnet at a local gym. They exchanged smiles and left without speaking, but later connected through Facebook. Their community, Basnet explained, was small and tightly connected, and a mutual friend had told Karki who she was.

Late-night phone calls followed, with the couple trading voice notes, TikTok videos, and long conversations that stretched past midnight. Within a year, Karki moved to Ohio to be closer to Basnet and his family.

Her parents initially opposed the relationship, worried about Karki's immigration status, education, and unstable employment. "They wanted me to marry someone with higher education, someone with a steady job," Basnet said.

Karki was required to report regularly to immigration authorities to renew his work authorization, a process that often left him in limbo. "I couldn't keep a stable job," he said. "Sometimes they delayed my permit." He eventually obtained his commercial truck driving license.

The couple eloped in December 2023. "I knew it wouldn't be easy for us," Basnet said. "I knew I might have to carry a lot on my own. But I couldn't love anyone else. He loved me deeply, and I knew he would make me happy for the rest of my life."

A Sudden and Devastating Turn

Asked whether she ever feared his deportation, Basnet said she believed the risk had passed years earlier. "We knew they tried to deport him in 2014, and neither Bhutan nor Nepal accepted him," she said. "He was born in a refugee camp. He had nowhere else to go. I felt confident they wouldn't deport him."

"He followed every rule," Basnet added. "I thought he was safe."

That sense of safety proved short-lived. After the 2024 election, reports began circulating that Bhutanese refugees were being picked up as ICE expanded enforcement in immigrant communities across the country. Only months earlier, the couple had been planning a future together, having saved nearly $20,000 for a down payment on a home.

"We wanted a small place of our own," Basnet said. "A room for our future kids." Within days, everything changed.

On April 2, 2025, the couple drove to what they believed would be a routine ICE check-in. When they arrived, an agent told Karki to return on April 8 instead. "I knew something was off," Basnet said.

They hired an attorney that morning after friends suggested that legal representation might prevent detention. It didn't work.

"When we walked in, they called my husband's name," Basnet recalled. "Before he could even step forward, agents grabbed him and handcuffed him."

Basnet and the attorney were ordered to wait outside. Minutes later, an agent returned and told them Karki would be transferred to the Butler County detention center and processed for deportation to Bhutan.

"I told them immediately he's not from Bhutan," Basnet said. "If he's deported there, he's not safe." The agent responded that the decision came from higher authorities and that travel documents had already been issued by Bhutan.

A Covert Deportation Process

Travel documents reviewed show that Bhutan has accepted deportees only as "non-Bhutanese," a designation that does not guarantee residency rights or legal status inside the country. Aisa Villarosa, an attorney with the Asian Law Caucus involved in ongoing Freedom of Information Act litigation tied to the removal of Bhutanese refugees, noted the unusual nature of these deportations.

"When you see a sudden shift in removal practices like this, it usually signals that some kind of government-to-government understanding exists," Villarosa said. "What we're trying to learn is what that understanding looks like."

She added that many Bhutanese refugees are being deported on commercial flights in what she described as a covert process that makes it "next to impossible" to track how many people have been removed.

In a statement, the UN refugee agency said deported Bhutanese refugees remain legally stateless because Bhutan does not recognize them as citizens and no other country claims them as nationals. Returning stateless people to a country that refuses to recognize them creates a precarious situation, the agency warned.

Detention and Deportation

Karki was transferred to St. Clair County Jail in Detroit on June 9, 2025, as his family, attorneys, and advocates fought for his release. "They treated us worse than animals," Karki said of his detention experience.

He described requesting to see an eye doctor because he had a prescription for glasses: "I asked the ICE nurse. They told me they would arrange it, but it never happened." He also reported harassment from other incarcerated individuals who targeted those detained for immigration violations.

After more than six months of legal challenges, including a habeas petition denied in December, Karki was placed on a commercial flight to Newark, then to New Delhi, and finally to Bhutan on January 13.

When Karki landed in India, local authorities escorted him through the airport. The next day, he was placed on a flight to Bhutan. "I had no documents with me," Karki said. "No ID to prove who I was."

When his plane landed in Paro, Bhutan, Karki said the weight of history finally caught up with him. "That's when it felt real," he said. "I grew up hearing stories of torture from my family and elders. When I stepped onto that ground, I thought I was going to die."

He said Bhutanese officials gave him two options on arrival: prison, or a taxi to the Indian border. He remains stateless, like many of the refugees deported before him.

A Mother's Fight Continues

Each day, Karki calls Basnet from his hiding place. They talk, cry, and sometimes laugh together. She continues to campaign for his return while raising their daughter alone. Basnet works full-time and often takes extra shifts while organizing, calling lawyers, and speaking at community events.

"I work as much as I can," she said. "Sometimes I leave my daughter with family and friends so I can keep fighting this."

Asked whether she is exhausted, Basnet shook her head. "I'm fighting for my family," she said. "For my husband. For the future of my daughter that's being stolen by the government."

Human rights organizations continue to raise alarms about the deportation of stateless individuals to countries that don't recognize them as citizens. John Sifton, Asia advocacy director at Human Rights Watch, emphasized the dangers: "It's not safe to be a stateless person. Refugees sent back to Bhutan are often pushed across the Indian border within days, leaving them stranded without nationality. That is an inherently risky and dangerous status to have."

Sifton added: "The idea that the U.S. government would now say the place they were expelled from is safe contradicts two decades of U.S. policy."

An advocacy group estimates that at least 70 Bhutanese refugees have effectively vanished into statelessness, some now in hiding, others stranded in legal limbo after being sent to a country that does not recognize them as citizens.

For Basnet, the deportation of her husband feels both personal and historical. "He doesn't have a home there," she said of Bhutan. "He doesn't have family. He doesn't speak the language. It feels like the history of expulsion is repeating itself, and no one seems to realize it."