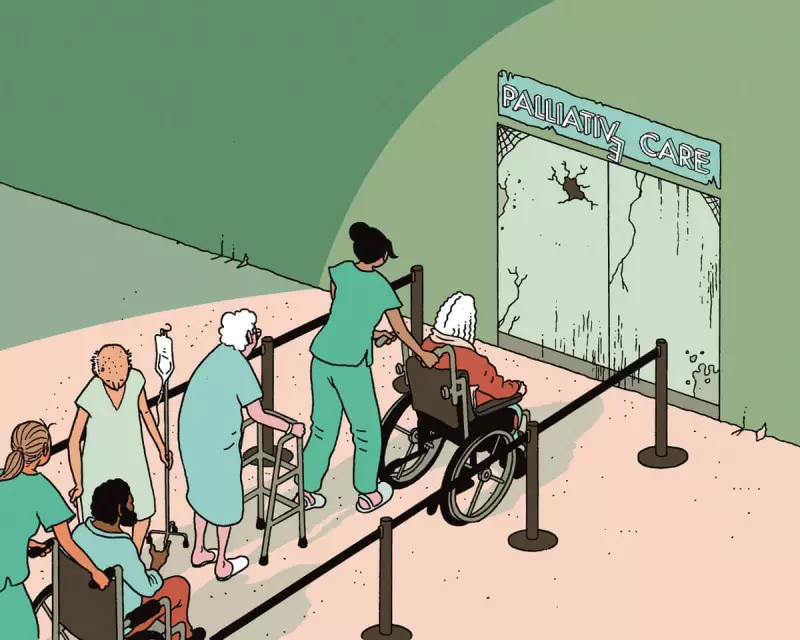

Britain is facing a devastating crisis in end-of-life care that leaves thousands of dying people without adequate support, according to palliative care specialists. While government attention focuses on assisted dying legislation, fundamental palliative care services are being systematically underfunded, creating a postcode lottery for those approaching death.

The shocking funding gap

The NHS funds only about 30% of hospice care across the UK, with the remaining 70% dependent on charitable donations. This represents a dramatic departure from the health service's founding "cradle to grave" principles, forcing local communities to fill gaps that should be covered by state funding.

A recent National Audit Office report revealed the dire financial situation facing hospices. Two-thirds of adult hospices in England recorded deficits in the 2023-24 financial year. The consequences are immediate and severe: hospices nationwide are cutting staff, reducing bed numbers, and slashing community services that allow people to die at home.

Real-world consequences for dying patients

The funding crisis translates directly into human suffering. Dr Rachel Clarke, an NHS palliative care specialist, describes witnessing elderly patients curled on trolleys in overwhelmed A&E departments when hospice beds aren't available. Families repeatedly hear the devastating words: "I'm sorry, there are still no beds at the hospice."

Approximately 150,000 people each year cannot access the palliative care they need. This shortage means more pain, more indignity, less choice, and reduced autonomy for people at their most vulnerable. The suffering at life's end now comes in two forms: the unavoidable part related to illness, and the entirely avoidable part created by political choices.

A postcode lottery of care

The situation has created dramatic regional disparities in end-of-life care. Last month, Arthur Rank Hospice in Cambridgeshire revealed that Cambridge University Hospitals had withdrawn £829,000 of annual funding, forcing the closure of nine out of 21 beds.

"Essentially, this now means that over 200 people a year will no longer have the option of being cared for in the comfort of our hospice and instead will sadly be dying in a busy hospital," stated CEO Sharon Allen. The NHS trust defended its decision by claiming the hospice beds represented "very poor value for money."

Your chances of receiving quality palliative care now depend on multiple variables, including local deprivation levels and whether your NHS management prioritises terminal patients.

Why we look away from death

Despite Britain's reputation for compassion and community spirit - demonstrated during the Ukrainian refugee crisis and COVID-19 pandemic - we collectively turn away from dying. Death has become unfamiliar and frightening in modern Britain.

Whereas Victorian England saw most deaths occurring at home, today less than a third of English deaths happen in domestic settings. The majority occur in hospitals, care homes, or - for a mere 5% - in hospices. This institutionalisation has made death's rhythms and rituals alien to most people.

Dr Clarke acknowledges her own former fear of death, recalling nights as a hospital house officer when she dreaded being called to the on-site hospice. Yet she emphasises that dying remains "one of the only experiences that all of us, without exception, will share."

The assisted dying dilemma

The timing of this crisis is particularly concerning as Kim Leadbeater's assisted dying bill progresses through the House of Lords. Politicians on both sides agree that high-quality palliative care should be available to anyone considering assisted dying, yet current reality falls dramatically short.

This creates a dystopian possibility: people might feel compelled to accept assistance in dying because they cannot access palliative care that could make life worth living. With demand for palliative care projected to increase by more than 25% by 2048, the situation threatens to worsen significantly.

The government's response to the National Audit Office report has been criticised as inadequate. Their statement mentioned "exploring how we can improve the access, quality and sustainability of all-age palliative care" in line with the NHS 10-Year Plan. However, examination of that plan reveals the word "palliative" appears only once throughout the entire document.

As Dr Clarke concludes, warm words simply don't cut it when people are suffering avoidable pain and indignity in their final days. The crisis in palliative care represents a fundamental failure of Britain's commitment to care for all citizens from cradle to grave.