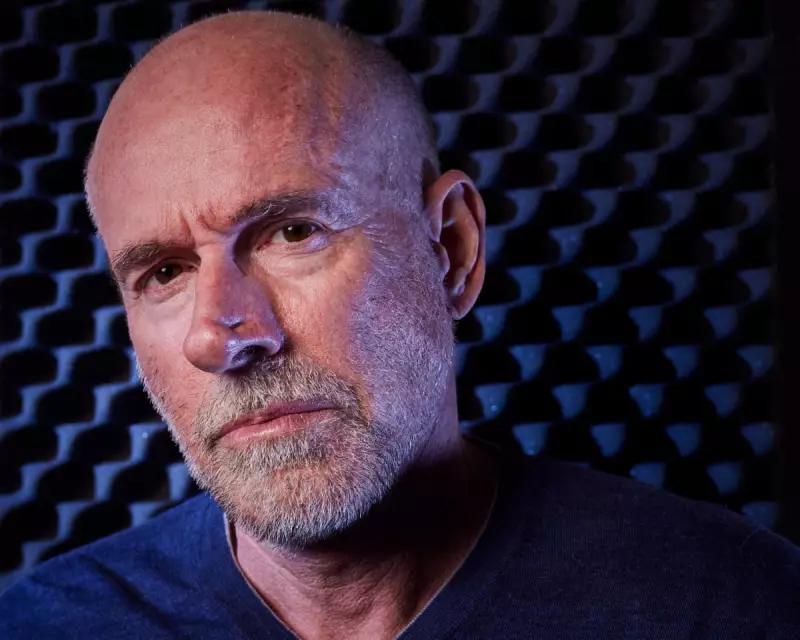

Marketing professor and author Scott Galloway has ignited a fresh conversation about the state of modern manhood in the UK. In a recent discussion centred on his new book, Notes on Being a Man, Galloway dissected what he terms a profound crisis of masculinity, pinpointing loneliness, shifting economic power, and a lack of positive guidance as core issues.

The Three Pillars of the Modern Male Struggle

Galloway, a professor at New York University's Stern School of Business, argues that traditional markers of male success and identity have eroded. He identifies three interconnected challenges facing men today. Firstly, an epidemic of male loneliness and isolation, exacerbated by declining community institutions and the digitalisation of social life. Secondly, the economic landscape has transformed, with sectors that once provided stable, masculine-coded employment diminishing, while sectors where women excel academically, like higher education, have expanded.

"Men are struggling to find their place in a new economic order," Galloway suggests, highlighting that this isn't about blame but about recognising a structural shift. The third pillar is a vacuum of constructive role models. Galloway contends that young men are often presented with toxic extremes online—hyper-aggression or passive nihilism—rather than healthy examples of integrity, resilience, and emotional maturity.

Prescriptions for a Healthier Masculinity

Moving beyond diagnosis, Galloway's book offers pragmatic advice. He emphasises foundational habits: physical fitness, financial responsibility, and nurturing deep platonic friendships. Crucially, he frames these not as pursuits of dominance, but of personal stability and capacity. "Being a good man is about being reliable, about showing up for the people in your life," he states.

He also tackles the sensitive topic of male-female relationships, urging men to move beyond resentment. Understanding the legitimate historical and contemporary grievances women face, he argues, is a step towards building more respectful and equitable partnerships. His perspective is one of self-improvement tied to communal benefit, advocating for men to become protectors and providers in a broader, more ethical sense—protecting the vulnerable, providing stability.

Broader Implications for British Society

The implications of this crisis, Galloway warns, extend beyond individual unhappiness. He links male disaffection to wider societal and political turbulence, including the rise of populist movements. A significant portion of the population feeling lost and without purpose, he implies, creates a fertile ground for polarisation.

His intervention adds to a growing UK discourse on men's wellbeing, challenging both simplistic nostalgia for outdated masculine norms and dismissive attitudes towards male-specific struggles. The call is for a nuanced, compassionate rebuild—creating new scripts for manhood that combine strength with vulnerability, ambition with empathy, and individual success with communal responsibility.

Ultimately, Galloway's analysis, detailed in his book launched in late 2025, is a stark reminder that the redefinition of masculinity is one of the UK's urgent social projects. The health of the nation's men, he concludes, is inextricably linked to the health of its families, communities, and political culture.