In a thought-provoking exchange published in the Guardian, two mental health professionals have challenged the fundamental direction of contemporary psychotherapy, arguing that the field remains trapped in outdated frameworks while neglecting more constructive approaches.

The Persistent Freudian Question

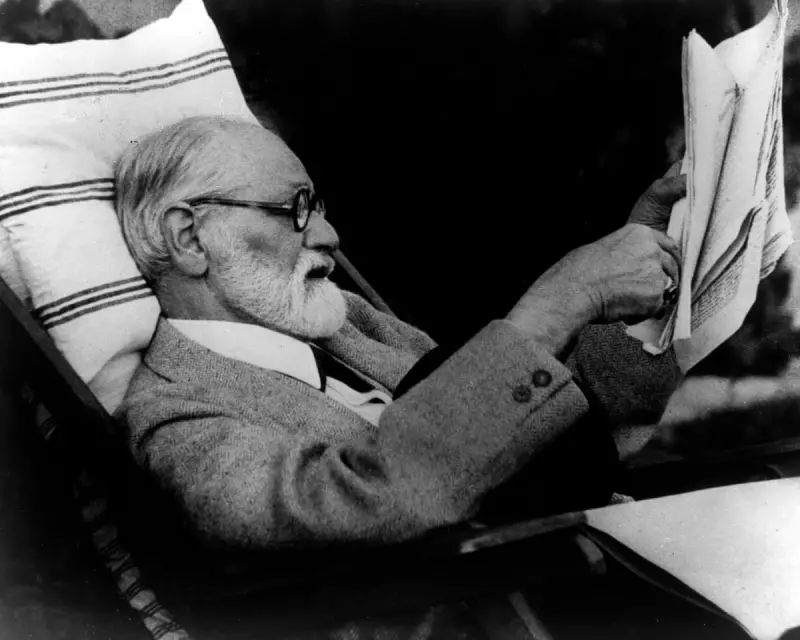

Dr James Taylor and Grendon Haines responded to Professor Raymond Tallis's review of Mark Solms's book The Only Cure, suggesting that the entire debate about whether neuroscience has vindicated Sigmund Freud misses the point entirely. They argue that psychotherapy's lack of scientific curiosity has become a significant barrier to progress in mental health treatment.

A Crisis of Curiosity in Psychotherapy

Dr Taylor, writing from Galashiels in the Scottish Borders, highlights what he describes as psychotherapy's "striking lack of curiosity." He notes the field's paradoxical position: claiming interest in human experience while simultaneously resisting rigorous scientific investigation.

"The field's insistence that 'it works' and 'research can't be done' is counterintuitive, given its positioning as interested in people," Taylor observes. He suggests that creativity and imagination, hallmarks of active scientific disciplines, could easily generate meaningful research questions.

Taylor proposes several potential research avenues that psychotherapy could explore:

- Comparing psychodynamic psychotherapy with conversations with untrained individuals

- Evaluating therapy against the benefits of a weekly gym membership

- Assessing long-term versus short-term therapy outcomes

- Comparing therapy with evening education classes

- Testing therapy against waiting list controls

- Examining therapy versus direct cash transfers in an era of financial strain

"Generating these ideas is not hard," Taylor notes. "Implementing them requires discipline." He identifies curiosity, creativity, and discipline as the essential foundations of science that should be applicable to psychology but appear conspicuously absent from psychodynamic approaches.

The Adlerian Alternative

Grendon Haines, writing from Montreal with over fifty years of experience applying Adlerian psychology, offers a fundamentally different perspective on mental health treatment. He argues that the entire Freudian debate represents a distraction from more important questions about human wellbeing.

"Whether brain imaging confirms Freudian hypotheses or psychoanalysis meets clinical trial criteria doesn't address the fundamental question: does this approach help people live more fulfilling, socially connected lives?" Haines questions.

He contrasts Solms's deterministic framework, which positions individuals as "passive victims of their buried past," with Alfred Adler's century-old recognition that people are active interpreters of their experiences, capable of reconstructing meaning through insight and conscious choice.

What's Missing from the Conversation

Haines identifies a crucial omission in Solms's defence of Freudian approaches: any consideration of community, social contribution, or cooperative relationships. He describes the Freudian focus as "relentlessly introspective" – concerned with internal drives, buried conflicts, and aggressive impulses rather than social connection.

Drawing on Canadian historian C.B. Macpherson's concept of "possessive individualism," Haines characterises the Freudian approach as promoting an atomised self wrestling with internal demons rather than recognising humans as social beings who find meaning through connection and contribution to others.

Time for a Paradigm Shift

Both correspondents suggest that psychotherapy needs to move beyond its Freudian preoccupations. Haines poses the central question that he believes the field should be addressing: "Why we keep trying to salvage a system that pathologises human nature when we have approaches that encourage human potential."

With nearly ninety years having passed since Freud's death and a century since Adler's departure from his circle, these experts suggest it might finally be time for psychotherapy to embrace new directions that focus less on pathology and more on human flourishing.

The letters highlight a growing tension within mental health treatment between traditional psychoanalytic approaches and more contemporary, evidence-based, and socially-oriented perspectives. As the field continues to evolve, this debate raises important questions about what constitutes effective mental health care in the twenty-first century.