Parenting Adult Children: A New Era of Extended Adolescence

Adolescence is no longer confined to the teenage years; recent neuroscience from Cambridge University suggests it can stretch into the early 30s. This revelation, published in Nature Communications, challenges traditional views that maturity ends at 18 or 25, highlighting a prolonged phase of vulnerability and opportunity for young adults. For parents, this means the journey of raising children evolves rather than concludes, yet it remains one of the least discussed aspects of family life.

The Crisis of Transition: A Personal Story

When my daughter turned 18, our relationship descended into a painful crisis that lasted far longer than I anticipated. As a psychotherapist trained in development, I felt utterly lost. Decades later, recalling that time still brings a flood of distress. My daughter, now a mother herself, describes that era as one of fury, desperation, and loneliness. She fought with us in ways no one in the family had before, screaming during walks and shattering our image as a happy family.

I questioned everything: Why didn't I see this coming? What did I do wrong? How could I fix it? Searching for guidance yielded almost nothing, leaving me to navigate this new terrain alone. With time and therapy, we survived those fights and rebuilt a close relationship. The breakdown became a breakthrough, resetting boundaries and fostering honest communication, though the process was chaotic and raw.

The Shift to Emerging Adulthood

In past generations, adulthood meant cutting ties at 18—leaving home, getting a job, and marrying young. Today, the path is slower, with many parents viewing their children's delayed independence as arrested development. Psychologist Jeffrey Arnett coined the term "emerging adulthood" for the 18 to 25 age range, a phase of exploration and uncertainty. This is not a moral decline but a developmental shift driven by technology, social change, and economic realities.

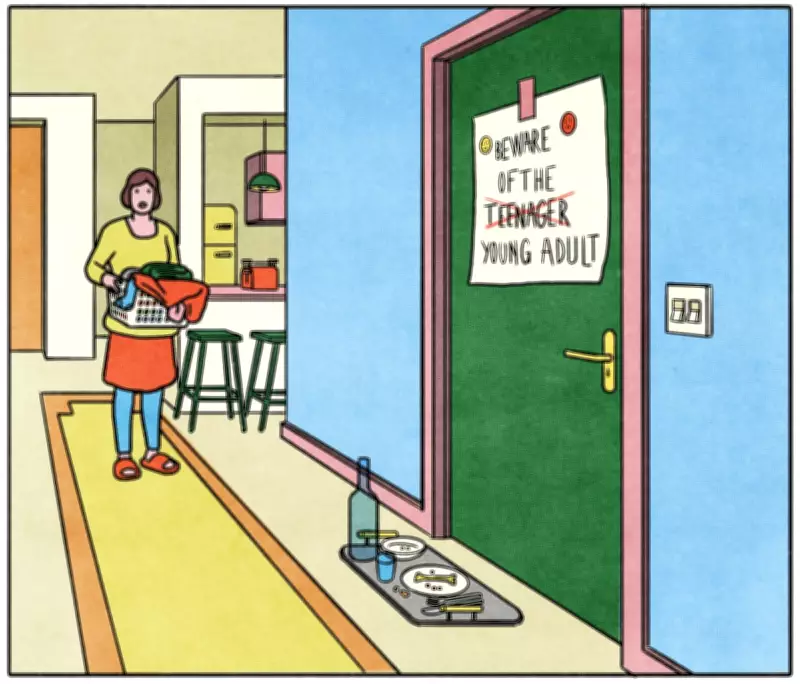

Statistics underscore this change: about a third of young adults aged 18 to 34 live with their parents, and nearly 60% of parents provide financial support. This adaptation to a transformed world often leaves parents feeling drained, yet it's rarely discussed openly.

Case Study: Sarah and Tom

Consider Sarah, a client in her mid-50s, who came to therapy feeling depleted. Her son Tom, 26, had moved back home after university, and what began as a temporary arrangement hardened into a stagnant dynamic. Tom worked part-time, contributed nothing to household costs, and resisted change, while Sarah cooked, cleaned, and tiptoed around his moods, straining her marriage.

Through therapy, Sarah realised her anxiety drove her behaviour. She had overcompensated for her own mother's coldness by protecting Tom from struggle, leaving him without confidence in his capabilities. The breakthrough came when Sarah set boundaries: she stopped doing his laundry and asked for financial contributions. Tom was furious initially, but gradually, he adapted, picked up more shifts, and discussed moving out. The atmosphere lightened, and Tom even thanked her for dinner—a small gesture that symbolised a shift from anxious management to respectful witnessing.

Guiding Principles for Parenting Adult Children

Research shows that when adult children return home, parents' wellbeing often declines, yet silence keeps everyone trapped. To navigate this, consider these principles:

- Clarity Over Control: Have explicit conversations about money, chores, privacy, and expectations. Boundaries prevent conflicts rooted in unspoken assumptions.

- Trust and Autonomy: Shift from fixing problems to trusting your child to navigate their life. Studies link excessive parental involvement, or "helicopter parenting," to lower self-confidence and mental health issues in young adults.

- Respect Developmental Stages: Ensure the relationship evolves to match their age, avoiding patterns from their teenage years. Young adults value clear expectations, meaningful contributions, and exit plans.

Challenges and Rewards

This transition is tough, requiring deep psychological work to love the child as they are, not as we imagined. As Anna Freud noted, "A mother's job is to be there to be left." Good-enough parenting balances connection without dependency, letting go of control while maintaining love.

Challenges include unprocessed trauma, which can echo across generations, and diverging worldviews on politics or lifestyle. Humility and curiosity are key—ask rather than tell, and allow differences without risking the relationship.

Despite complexities, this stage offers profound rewards. Conversations grow richer, humour deepens, and you can enjoy your children as individuals. One mother described it as "watching your heart walk around outside your body, but now it walks confidently." Turning a bond of dependency into mutual respect is a remarkable achievement.

Conclusion: A Mature Love

Parenting does not end; it matures. This extended adolescence calls for courage to learn, forgive, and show up consistently—not as an all-knowing parent, but as a fellow human being who continues to grow. Families are living systems that adapt, and staying open to listening and loving, even when it's hard, is the best we can do.

For my daughter, feeling heard was transformative. "Over time my rage decreased as I felt heard enough," she says. "I learned I was loved as I am." This journey, though messy, underscores that love can thrive through evolution and honesty.