Fury Over Closure of 'Vital' Emergency Sickle Cell Unit in London

The closure of a specialised emergency unit for sickle cell disease at The Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel has sparked outrage among patients and advocates, who describe it as a crucial lifeline for those battling the deadly blood disorder.

What Was the Emergency Sickle Cell Unit?

The Emergency Sickle Cell Day Unit operated as a six-month pilot scheme, providing rapid, specialised crisis treatment for patients experiencing acute pain episodes known as crises. Unlike standard A&E departments, the unit offered targeted care specifically designed for sickle cell emergencies.

Sickle Cell Disease is the fastest-growing blood disorder in the United Kingdom. It causes red blood cells to become sickle-shaped, leading them to stick together and block blood vessels. These blockages trigger extreme pain and can prove fatal without prompt medical intervention.

The condition predominantly affects individuals of African and African-Caribbean heritage, though it can occur across all ethnic backgrounds.

Patient Experiences Highlight Dramatic Benefits

Delo Biye, a 47-year-old from Sidcup who has sickle cell disease, used the emergency unit seven times during its trial period. He described the service as "life-changing", noting that treatment could be administered within 15 minutes of arrival.

"It's made a huge difference. First of all, you can go and call the unit in the morning to check for room and they'll say yes. You're not going there to wait for hours on end. I know that within 15 minutes they'll give you what you need - so you can imagine the difference between that and A&E," Mr Biye told reporters.

He contrasted this with standard emergency departments, where over 452,000 patients across England waited 12 hours or more for a bed between January and October last year. "A lot of people won't go to A&E because they don't want to wait 12 hours, even though they might be in agony. There's no comfort in A&E if you're well, let alone if you're in agony," he added.

Community Leaders Decry Closure Decision

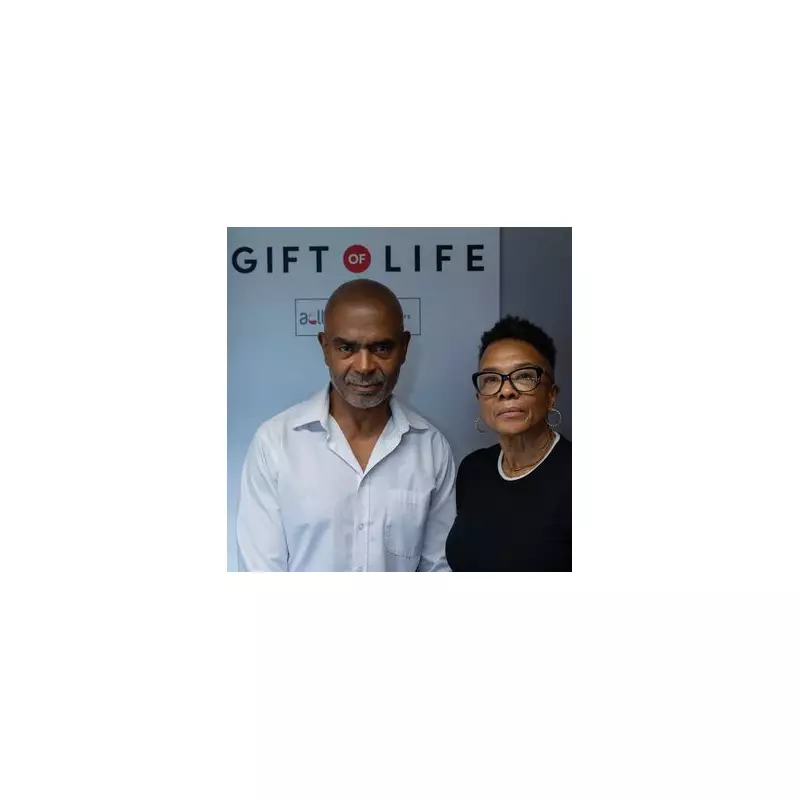

Beverly De-Gale OBE and Orin Lewis OBE, co-founders of the African Caribbean Leukaemia Trust, have strongly criticised the trust's decision to discontinue the service. They described the unit as a "vital" lifeline for those living with the disease.

Mr Lewis expressed concern about systemic bias, stating: "This unit is needed urgently for this cohort of patients, or warriors, who need specialist treatment or care outside of going to the usual A&E routes. If it was white people being affected by this, the system would be totally different - there is inherent bias."

Ms De-Gale highlighted the growing prevalence of the condition, noting: "Sickle cell is the fastest growing blood disorder, 300 babies are born each year with the disease. It is the pilot clinic they want to close down - why would they close it down after six months when it's so vital?"

NHS Trust Responds to Criticism

A spokesperson for Barts Health NHS Trust acknowledged the strong support for the pilot scheme, stating: "We recognise the strength of feeling and support that our same day emergency care (SDEC) pilot has received, which is a testament to the hard work of our teams."

The trust explained that the pilot, funded by the North East London integrated care board, aimed to test alternative treatment pathways for sickle cell patients experiencing acute pain. It ran from September 2025 to the end of January 2026 to evaluate impact and inform future service planning.

"There is no change to the way we manage patients with sickle cell disease, and our Haematology Day Unit remains open for all our elective transfusion therapies. Patients with sickle cell disease will continue to receive specialist-led care at our hospital," the spokesperson added.

The trust emphasised its commitment to improving pain management pathways for both acute and chronic sickle cell disease cases, pledging to continue welcoming community input into service design.

Growing Campaign to Save the Service

In response to the closure announcement, Delo Biye has launched a petition that has already garnered nearly 35,000 signatures. He argues that London needs a permanent Emergency Sickle Cell Unit to ensure patients can access necessary treatment without dangerous delays.

"We need it and you just took it away. The cynical part believes it's a tick box exercise - I mean what is the point in it?" Mr Biye questioned, reflecting the frustration felt by many in the sickle cell community.

The controversy highlights ongoing challenges in providing equitable healthcare services for conditions that disproportionately affect minority ethnic communities, with advocates calling for sustained, specialised support rather than temporary pilot schemes.