On a cold winter afternoon at the Royal Stoke University Hospital in Staffordshire, thirteen ambulances sit in a line behind the Emergency Department. Inside each vehicle, a patient waits, some for over four hours, just to get through the door. This scene, witnessed by The Guardian during a rare visit, encapsulates the intense pressure gripping Britain's National Health Service.

A System Under Maximum Pressure

Deputy medical director Ann-Marie Morris surveys the scene, squinting in the low sun. The reason for the queue is simple: there are no beds available inside the Emergency Department. The hospital's 1,178 beds are all occupied, with an additional 15 patients being treated in ED corridors and 20 more in similar situations on other wards. The trust's Operational Pressure Escalation Level (Opel) is at 4, the highest possible rating before declaring a critical incident.

"This is busy," says Morris. "This is not our worst day, but equally… it is a challenge to manage." For the staff at this major regional NHS hub, it is a day of huge logistical headaches and personal stress, yet also a typical winter Tuesday. The NHS faces exceptional strain this week, with an unprecedented early surge in flu cases colliding with a five-day strike by resident doctors.

Frontline Ingenuity in a 'Permacrisis'

For the battle-hardened staff, these are just further complications in what matron for general surgery Dan Hobby describes as a permanent state of emergency. "It would be fair to say I don't think we're ever out of winter," Hobby remarks. "It almost feels like winter is 12 months a year. We are permanently in winter."

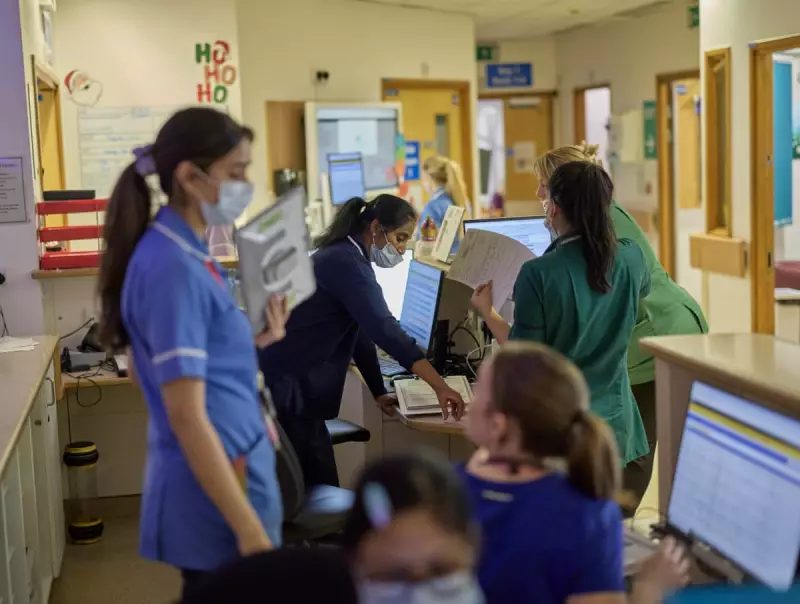

The hospital invited The Guardian to see how staff manage patient flow through a gridlocked system, one bed at a time. On a respiratory ward, consultant Dr Ashwin Rajhan explains the daily scramble. That morning, four patients in ED needed non-invasive ventilation (NIV), but his 28-bed ward, with a 20-patient NIV capacity, was already at 21.

"We had to go through all the patients individually, get the physios on board and ask them to see the patients urgently to get them in a place to leave," Rajhan says. Even ward computers failing added to the delay, requiring a discharge facilitator to physically fetch an IT technician. Every cleared bed creates a ripple effect, freeing space in ED and ultimately allowing an ambulance to collect another patient.

Institutional Gridlock and Human Cost

Despite initiatives like "admission avoidance" clinics and "virtual wards" for home follow-ups, institutional blockages persist. On the critical care ward, patient Tracey Wootton has been waiting for a transfer to a general medical ward for three days, far exceeding the national four-hour standard.

The Surgical Assessment Unit (SAU), which handles specialities from ENT to gynaecology, is also overwhelmed. Since losing a ward in October, transfer waits have stretched from 24 hours to three days. With a capacity of 30 but currently holding 55 patients, some are forced to wait on plastic chairs. "It isn't ideal," admits senior staff nurse Molly Merrison.

In a windowless operations room, clinical head of operations Becky Ferneyhough monitors real-time data on patient flow. By 5 pm, the queue of ambulances had grown to 20. "We've had a very difficult afternoon," she confirms. She stresses the human toll behind the numbers: "The patient is the most important part of everything that we do… Some of those decisions are really, really difficult to make."

As the NHS weathers this perfect storm of flu, industrial action, and chronic capacity issues, the dedication of staff at hospitals like Royal Stoke remains the system's crucial bulwark. The big question looming is whether the early flu surge will subside or, as many fear, return with a vengeance after Christmas gatherings.