National Portrait Gallery's Freud Exhibition Faces Critical Scrutiny

The National Portrait Gallery in London is currently hosting a major exhibition titled Lucian Freud: Drawing into Painting, which has sparked considerable debate among art critics and visitors alike. Running from 12th February to 4th May, this comprehensive showcase attempts to trace the artistic journey of one of Britain's most celebrated modern painters, but according to many reviewers, it ultimately presents a confusing and often disappointing narrative.

The Stark Contrast Between Mediums

Freud's reputation as a master painter remains unquestioned, with his monumental oil paintings continuing to command awe and admiration. The exhibition does include several of these powerful works, such as his iconic 1990s portrait of Sue Tilley, the Benefits Supervisor. This particular painting demonstrates Freud at his absolute peak, transforming the human form into what one critic describes as an ecstasy of oily greys, whites, purples, capturing every pore and blemish with breathtaking intensity.

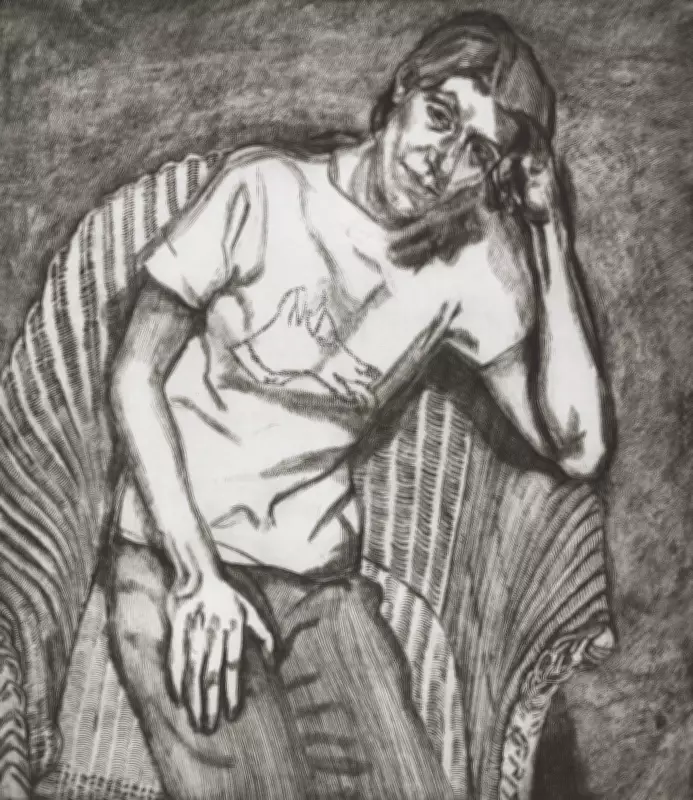

However, the exhibition's primary focus lies elsewhere, concentrating heavily on Freud's drawings, sketches, and etchings. This is where the show encounters significant problems. The drawings range from what critics politely term ordinary to frankly awful, lacking the daring and technical brilliance that characterise his painted works. Etchings like Solicitor's Head from 2003 and Man Posing from 1985 are presented as important late-career pieces, but they often appear laborious and precious rather than innovative.

Questionable Curatorial Choices

The exhibition structure itself has come under fire for what many perceive as indulgent and confused curation. By including childhood crayon drawings from Freud's Berlin years alongside meticulous but ultimately sentimental portraits from the 1940s and 50s, the show creates a narrative that some argue diminishes rather than enhances the artist's legacy. The early drawings of figures like Kitty Garman reveal a softer, more conventional artist than the brutal psychological examiner he would later become.

Critics point to a fundamental rift in the exhibition that occurs when it documents Freud's decisive shift in the 1960s. At this point, he largely abandoned drawing to immerse himself completely in painting. Works like his terrifying 1963 Self-Portrait mark this transformation, showcasing the raw, instinctive power that would define his greatest achievements. The exhibition seems to celebrate the earlier, more careful draughtsman while downplaying the revolutionary painter he became.

The Risk to Freud's Artistic Legacy

Perhaps most concerning is the potential impact such exhibitions might have on Freud's standing in the art historical canon. By emphasising his less accomplished works and presenting him as a minor British artist of careful drawings rather than the monumental painter of flesh and psychology, curators risk redefining his legacy in troubling ways. Some reviewers have suggested that if Freud's great paintings are indeed difficult to borrow from private collections, institutions should reconsider mounting exhibitions that cannot properly represent his genius.

The overall impression left by Drawing into Painting is one of missed opportunities and perplexing priorities. While it offers moments of brilliance when Freud's paintings appear, these are surrounded by what one critic bluntly calls dross. For visitors hoping to understand why Freud remains such an important figure in modern art, this exhibition may prove more confusing than enlightening, highlighting his struggles with certain mediums rather than celebrating his extraordinary achievements with others.