In the shattered remains of a Tehran apartment block, struck by missiles in June 2025, a single, scarred book lay among the dust and concrete. For translator Amir Mehdi Haghighat, this was no ordinary text. It was his own work, a Persian translation, surviving the devastation that threatened to erase everything. This moment crystallised a profound truth: translation is an act of resistance, a stubborn refusal to let stories disappear.

A City Under Fire: The Night the Bombs Fell

The assault began without warning on 13 June 2025. Israeli missiles struck the Iranian capital, severing internet connections and plunging districts into chaos. Haghighat was in his apartment, immersed in translating Jhumpa Lahiri's Translating Myself and Others, a meta-text on the very craft he was practising. As buildings crumbled around him, he edited passages on the endurance of meaning—a stark, ironic counterpoint to the violence outside.

His professional life halted instantly. A book ready for press was stranded at a shuttered printing house. Bookstores closed. One terrifying night, as blasts encroached, he and his family fled to a basement garage. His mind raced to his personal library: a lifetime's collection of dictionaries, rare volumes, and every book he had ever translated. "That library was my lifework," he recalled, "and I didn't know if I, or it, would survive the night."

Translating Destruction: Grief, Memory, and Art

The human cost was immediate and visceral. A photograph circulated of 23-year-old poet Parnia Abbasi, killed in the strikes, her final poem echoing online: "I will end / I burn / I’ll be that extinguished star." Haghighat witnessed an elderly woman with Alzheimer's, who had lost a son in the Iran-Iraq war decades prior, running through alleyways calling a name, the bombs resurrecting a buried grief.

Amidst this, small acts of defiance emerged. At his cousin's bomb-damaged home, a woman sat painting before the ruins, refusing to let silence win. The city's mood swung between fear, outrage, and numbness. For Haghighat, the bombardment also dismantled the practical tools of his trade. Without electricity or the internet, the instant searches and references vital to a translator vanished.

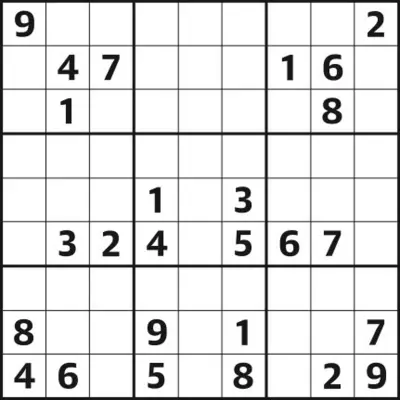

The Image That Changed Everything: A Scarred Book Endures

A week into the attacks, Haghighat was translating James Thurber's Many Moons, a children's tale about reaching for the impossible. He pondered if the moon symbolised the seemingly unattainable peace everyone craved. Then, he saw the photograph.

On a news site, amid the rubble of another destroyed building, lay one of his old translations. The cover was torn and smudged, pages singed, but it was intact, his name clearly visible on the front. For a translator, often an invisible conduit, this was his work made starkly, physically present. "It was scarred, but surviving," he noted.

This powerful image brought home the political weight of his craft. Translating under bombardment became a statement that the original voice "mattered" and would not be erased. It echoed the resolve of Antonio Gramsci, whom Lahiri wrote about, who requested more dictionaries in his prison cell. For Haghighat, translation transformed from a literary task into a vital anchor. It is not merely carrying stories across languages, but ensuring they remain when everything else falls away.

The torn book in the ruins stands as a testament to the resilience of culture and the quiet, persistent power of words to outlast even the most violent upheaval.