We are living through what author Naomi Alderman calls the Information Crisis - the third major information revolution in human history following the invention of writing and the printing press. This digital era presents both unprecedented opportunities and significant challenges that affect us psychologically and socially.

The Historical Context of Information Revolutions

Alderman draws powerful parallels between our current situation and previous information revolutions. The invention of writing brought beautiful new ideas and moralities, but also introduced misreading and text-based warfare. The Gutenberg printing press led to the Enlightenment and scientific discovery, but first plunged Europe into the Reformation period where people were burned at the stake over doctrinal disputes.

This burning at the stake serves as a metaphor for how people in information crises can turn against their own values, treating living people as symbols to be cruelly punished to make a point. Alderman argues that attempting to eliminate all opposing opinions inevitably leads to human rights atrocities - a lesson history has taught us repeatedly.

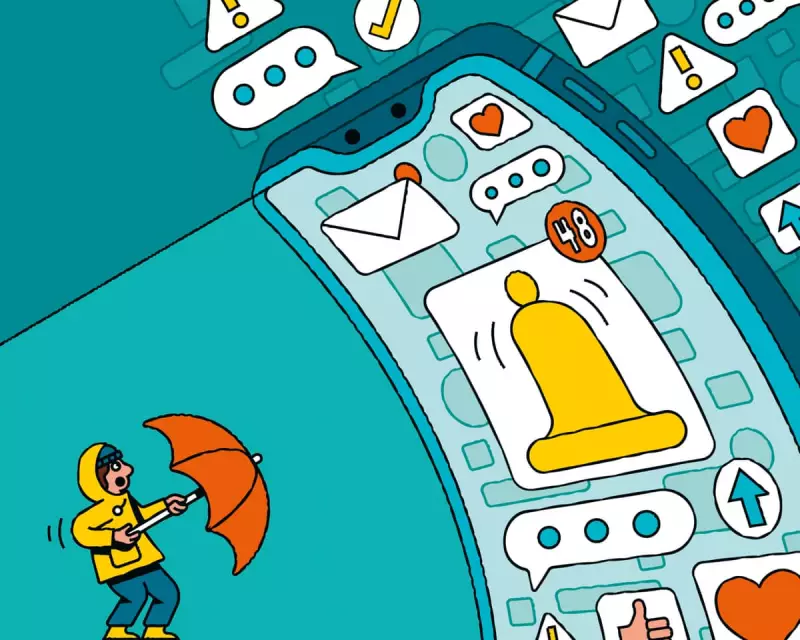

Why We Feel Overwhelmed and Angry

The digital information overload makes us anxious and angry for several key reasons. We're constantly exposed to how much we don't know, leading to situations where expressing an opinion online can result in being corrected by dozens of people. This creates feelings of being unsettled, frightened and out of touch.

Similarly, discovering that people we respect hold opinions we find objectionable creates what Alderman calls the Uncle Bob syndrome - where we question who we can trust and whether we're surrounded by upsetting idiots. This leaves us feeling isolated, misunderstood and angry.

Twelve Practical Strategies for Survival

Find trusted fact-checkers: Organisations like the BBC's fact-checking service, Snopes and PolitiFact provide reliable verification in an era of convincing fakes.

Notice your emotions before sharing: Strong feelings of glee or outrage should signal the need to verify information before spreading it.

Resist public shaming: When someone shares false information, send a private message rather than publicly embarrassing them.

Give institutions the benefit of the doubt: Look for organisations that acknowledge errors quickly and focus on systemic improvements rather than perfect, error-free information.

Avoid hate reading: Consuming content designed to enrage you creates pleasure through feeling superior, but destroys shared reality.

Recognise humanity: Treat people as thoughtful individuals with reasonable perspectives, not as symbols or imbeciles.

Ignore most opinions: Take people's emotions seriously but treat few non-expert opinions as important.

Use smartphones judiciously: Since devices aren't designed for wellbeing, implement your own limits on usage.

Limit social media exposure: Curate your feeds to preserve relationships by avoiding constant exposure to divisive political content.

Don't over-protect children: Create gradual on-ramps to digital content rather than sudden exposure to the full internet at age 13.

Campaign for better laws: Advocate for legislation that gives users control over their digital experiences and protects wellbeing.

Avoid pointless arguments: Alderman keeps herself honest with the reminder that not getting into pointless online arguments is an act of revolution.

Preserving Our Humanity in Digital Times

The core message throughout Alderman's advice is the importance of not treating people as symbols. She encourages considering that reasonable people may have useful truth on both sides of disagreements, and fundamentally urges: don't burn anyone at the stake today.

This means not trawling through decades of social media to find someone's worst statement, not trying to get people fired over disagreements, and not letting the worst behaviour of others become the standard for your own actions. The digital age may be overwhelming, but with conscious effort we can navigate it while maintaining our humanity and values.