Cambridge University has made a landmark announcement that promises to transform our understanding of one of Victorian Britain's most overlooked literary talents. The university has acquired and unsealed the personal archive of Amy Levy, the pioneering writer whose work explored women's independence, Jewish identity and same-sex desire more than a century ago.

A writer ahead of her time

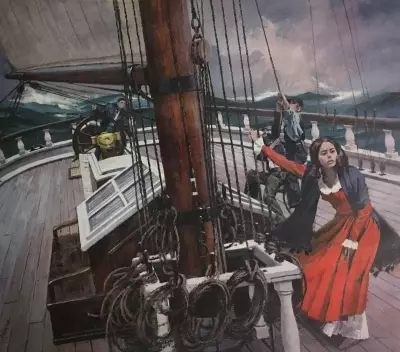

Born in 1861 into a middle-class Jewish family in London, Levy entered Newnham College, Cambridge in 1879, becoming only the second Jewish woman among Cambridge's first generation of female students. During her brief but remarkable career, she produced three poetry collections, three novels including Reuben Sachs and The Romance of a Shop, numerous essays and a series of articles for the Jewish Chronicle.

When Levy died by suicide in 1889 at just 27 years old, she was already recognised by contemporaries as an exceptional talent. Oscar Wilde wrote her obituary, praising the "sincerity, directness, and melancholy" of her work and hailing her as "a girl of genius".

Revealing the woman behind the words

The newly available collection, which until recently remained with a private corporation, offers unprecedented insight into Levy's intellectual and social circles. The archive includes letters, draft manuscripts, photographs, diary entries and even evidence that Levy paid a clipping service to send her all news coverage about her work.

John Wells, senior archivist at Cambridge University Library, emphasised the significance of this discovery. "It's rare nowadays for a coherent corpus of a 19th-century author's papers to come to light," he said. "We were determined to take the opportunity to make her archive available in the place where she studied and where she visited even in the last months of her life."

Contemporary relevance of a Victorian voice

Researchers believe Levy's work speaks directly to modern conversations around feminism, LGBTQ+ literature and Jewish identity. Professor Linda K Hughes of Texas Christian University, who is working on a book about Levy, explained why the writer remains so compelling today.

"Not only was she a fine and evocative writer, but she was also so complex," Hughes said. "She affirmed her Jewish identity, but she was also an atheist. She seemed to get along very well with men, but she was a queer woman."

The archive reveals Levy's social network at Newnham and her later connections through Vernon Lee (the pen name of Violet Paget), who introduced her to Wilde's circle. "Levy entered Lee's circle, in fact she fell in love with her, a love that unfortunately was never returned," Hughes noted.

The collection includes Levy's 1889 appointment diary, where increasingly sparse entries trace her final months. A moving final entry, written the day before her death, simply states: "Alone at home all day." Yet Hughes emphasises that Levy also experienced "a rich, full, exciting existence" and "could be humorous at times".

Levy faced multiple challenges including neuralgia, increasing deafness that led to social isolation, and depression. "Though she never quite found happiness," Hughes observed, "it was always something she insisted on: the right to be happy, even ecstatic."

This remarkable archive not only promises to enrich academic scholarship but also offers connection for contemporary audiences grappling with many of the same issues Levy explored in her pioneering work over a century ago.