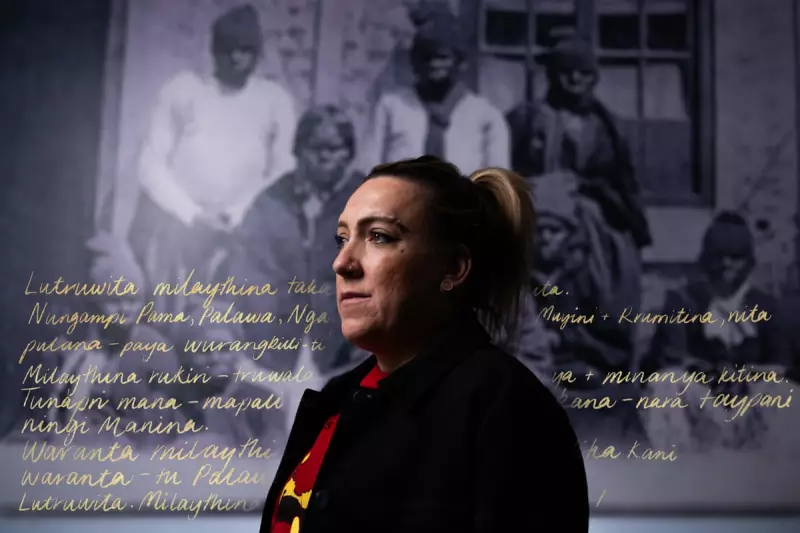

In Launceston, Daisy Allan stands before a powerful relic of history: an 1858 photograph of Trukanini and other Palawa survivors. Under their gaze, she speaks in a language that was once declared extinct. This is palawa kani, the painstakingly reconstructed tongue of the Tasmanian Aboriginal people, now being spoken by a new generation for the first time in over a century and a half.

A Legacy of Survival and Resistance

The photograph in the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre is a stark reminder of a brutal past. It shows survivors from Wybalenna, a desolate internment camp on Flinders Island where hundreds were exiled in the 1830s. Of the 300 sent there, only 47 lived. The genocide of the Palawa people was so severe that when Trukanini died in 1876, she was incorrectly declared the last Tasmanian Aboriginal person.

"It just goes to show the resilience and the resistance of Tasmanian Aboriginal people," says Allan, a language worker. "That we can stand strong against all odds, take pride in ourselves, refuse that push that we don't exist, that we don't have a language."

Today, the situation is transformed. Unlike Allan's parents' or grandparents' generations, Palawa children are now born hearing the sounds of their ancestral language. Weekly lessons in schools, language modules for all stages of life, and community use have breathed life back into a linguistic heritage once thought lost forever.

The Daunting Task of Reconstruction

The journey to revive palawa kani began over 30 years ago, led by figures like June Sculthorpe. The task was monumental. The Aboriginal population had plummeted from between 5,000 and 10,000 in 1803 to fewer than 100 by the late 1830s. While some single words survived in common use, full sentences were incredibly rare.

A crucial resource was the journals of George Augustus Robinson, the so-called "conciliator" who documented vocabulary and placenames even as he facilitated the devastating round-up of Aboriginal people. His records, alongside those of over 70 other settlers, became a vital, if troubling, archive.

Another key was the crackling sound of wax cylinder recordings. Sculthorpe would visit the Tasmanian Museum as a child to hear her great-great-grandmother, Fanny Cochrane Smith, who was born at Wybalenna in 1834, sing and speak. These recordings, made in 1899 and 1903, preserved precious fragments of sound.

Linguistic analysis concluded that while there were once at least eight distinct language groups, there wasn't enough of any single one to revive it fully. The community made a pivotal decision: to amalgamate the remnants into one authentic, reconstructed language, much as their ancestors had blended languages at Wybalenna.

A Labour of Love and Linguistic Rigour

The result is not a "made-up" language, but the product of more than 30 years of dedicated research by over 30 people. The team, which includes Theresa Sainty, analysed historical recordings to isolate sounds, developed a unique spelling system, and meticulously documented the history of every single word to justify its inclusion.

"We weren't really thinking that we would ever revive a language," Sculthorpe reflects. "I think we amaze ourselves sometimes. There we were – not only were we as a people on the brink of extinction – but here we are now, a thriving people with our own language."

The work has extended to reclaiming the landscape itself. Sixteen palawa kani placenames have been officially gazetted under dual naming policies. The Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre has also produced a comprehensive online map of Lutruwita (Tasmania) detailing the linguistic history of locations.

Language as Activism and Identity

For those involved, language revival is a profound act of cultural sovereignty and resistance. Theresa Sainty, now working on a PhD about language sovereignty, describes it as activism. "Writing songs, writing poetry, speaking at events, it's activism," she says. "And language is such a powerful and empowering tool to use."

Annie Reynolds, the palawa kani program coordinator, notes that the core vocabulary retrieval is nearly complete. The focus has now decisively shifted to community engagement—encouraging Palawa people to speak the language daily and urging all Tasmanians to use the reclaimed placenames.

Daisy Allan's favourite is Lumaranatana, the country around Cape Portland, a name recorded by Robinson from two Aboriginal women. "That's the country of the women who survived who make up today's Aboriginal community," she says, linking the past directly to the present.

From the brink of cultural erasure, the Palawa people have performed an extraordinary feat of reclamation. The sound of palawa kani, silent for 150 years, now echoes once more—a testament to unyielding resilience and a reclaimed future.