The Unheard Cry: How a Black Abolitionist Confronted the Monarchy Over Slavery

In the autumn of 1786, a remarkable parcel arrived at Carlton House, the London residence of George, Prince of Wales. It was sent by Quobna Ottobah Cugoano, a free Black man living in the city, one of approximately 4,000 people of African descent in London at that time. Inside were pamphlets detailing the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade and the brutal treatment of enslaved individuals in Britain's Caribbean colonies. The accompanying letter, signed under his alias "John Stuart," implored the heir to the British throne to read the enclosed "little tracts" and consider the plight of Africans who were "most barbarously captured and unlawfully carried away from their own country." Cugoano warned that Africans were treated "in a more unjust and inhuman manner than ever known among any of the barbarous nations in the world."

A Unique Position of Proximity to Power

At this time, Cugoano was employed as a domestic servant by the fashionable painters Maria and Richard Cosway, whose home at Schomberg House on Pall Mall stood just two blocks from Carlton House. Richard Cosway had recently been appointed principal painter to the Prince of Wales, making their residence a hub for artists, aristocrats, and politicians, with weekly salons and concerts sanctioned by the prince himself. This employment granted Cugoano something rare for a former enslaved man: regular, direct access to Britain's elite and the royal family. He used this proximity to full advantage, observing the Prince of Wales's vanity and ambition, which he later tailored his appeals to exploit.

From Enslavement to Activism in London

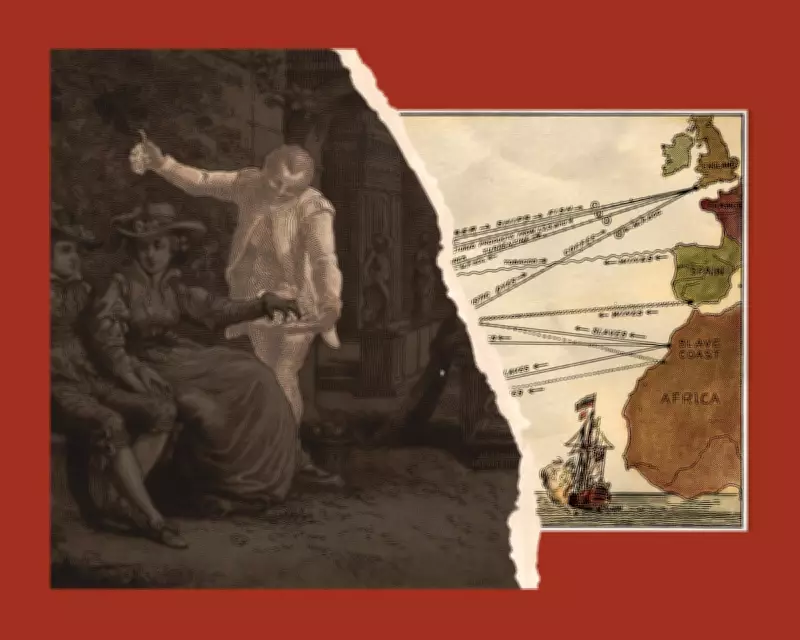

Born around 1757 in a Fante village in what is now Ghana, Cugoano's childhood was abruptly ended when slave traders raided his community. At age 13, he was kidnapped, marched in chains to the coast, and forced onto a slave ship, enduring a terrifying Atlantic crossing he described as a "state of horror and slavery." After nearly two years of labour on a plantation in Grenada, he was brought to England in late 1772, shortly after Lord Mansfield's ruling in the Somerset case, which many mistakenly believed granted freedom upon touching English soil. Cugoano claimed his liberty, was baptised at St James's Church in Piccadilly under the name John Stuart to avoid re-enslavement, and embedded himself in London's free Black community. By the mid-1780s, he had joined the Sons of Africa, a group of Black activists who lobbied MPs and rescued free Black people from illegal seizure.

Direct Appeals to the Monarchy and Their Aftermath

Cugoano understood that abolishing the slave trade required royal support or at least acquiescence. In his letter to the Prince of Wales, he promised that if the prince used his future power to end the "iniquitous traffic of buying and selling men," his name would "resound with applause from shore to shore" and be held "in the highest esteem throughout the annals of time." The following year, he sent the prince a copy of his book, Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species, the first anti-slavery treatise written by a formerly enslaved African in Britain. He also sent a copy to King George III, appealing to Christian duty and moral responsibility, while indicting the monarchy for centuries of profiting from slavery. The Prince of Wales kept the book in the royal collection but took no action, and the king remained silent.

The Legacy of Silence and Radical Demands

Cugoano's arguments were radical for their time, demanding immediate abolition, universal emancipation, and political inclusion for Black people. He warned that unless George III intervened, divine retribution would follow, a stance white abolitionists avoided. His book initially attracted little attention, but by 1791, an abridged edition gained influential subscribers, and the abolition movement he helped build gathered momentum. Cugoano himself vanished from historical records soon after, but his book remains in the royal collection, a testament to the monarchy's missed opportunity for moral leadership. This silence echoed for generations, confronting the royal family with its complicity in the slave trade and its failure to act on a direct plea from a survivor of that system.