Thirty-five years ago today, one of Britain's most transformative prime ministers made an emotional exit from Downing Street. Margaret Thatcher left office on 28 November 1990, marking the end of an era that had reshaped the nation.

The Final Act

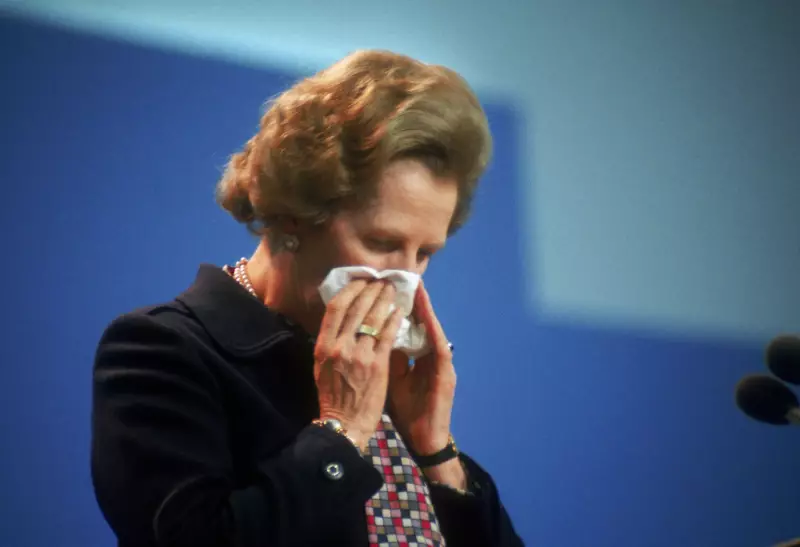

Thatcher delivered a brief, tearful speech outside Number 10 before being driven to Buckingham Palace for her final audience with Queen Elizabeth II. After tendering her resignation, John Major arrived just 15 minutes later to be appointed as her successor.

The Iron Lady had served as Prime Minister for more than 11 years, famously telling the BBC's John Cole in 1987 that she hoped to "go on and on". Her supporters could rightly claim she had never lost an election since entering Parliament for Finchley in 1959. Yet her departure was anything but voluntary.

The Gathering Storm

Trouble had been brewing within Conservative ranks for at least two years. The introduction of the Community Charge in 1989-90, quickly dubbed the "poll tax", proved violently unpopular. This fixed-per-person charge replaced domestic rates and was seen as deeply unfair, drawing comparisons to the hated measure that helped spark the Peasants' Revolt of 1381.

Simultaneously, Thatcher was growing increasingly isolated from senior colleagues, particularly on European policy. In June 1989, Chancellor Nigel Lawson and Foreign Secretary Sir Geoffrey Howe threatened resignation unless she committed to joining the European Exchange Rate Mechanism. Though she avoided setting a date, the confrontation left relationships fractured.

The Prime Minister soon moved Howe from the Foreign Office to Leader of the House of Commons, while Lawson resigned in October after clashing with Thatcher's economics adviser Sir Alan Walters.

The Regicide Speech

The final blow came from an unexpected source. Sir Geoffrey Howe resigned on 1 November 1990 after nearly 16 years of service. His resignation speech in the House of Commons two weeks later would prove devastating.

In quiet, measured tones, Howe described Thatcher's Eurosceptic comments as "background noise" that undermined colleagues. His cricket analogy became legendary: "It is rather like sending your opening batsmen to the crease only for them to find... that their bats have been broken before the game by the team captain."

Most crucially, Howe declared: "The time has come for others to consider their own response to the tragic conflict of loyalties." This was widely interpreted as an open invitation to challenge Thatcher's leadership.

The very next day, Michael Heseltine announced his candidacy. The former Defence Secretary had been a brooding presence since his 1986 resignation over the Westland affair.

The Endgame

In the first leadership ballot on 20 November, Thatcher led Heseltine 204 votes to 152 - just four votes short of the margin needed for outright victory. Returning from a summit at Fontainebleau, she declared "I fight on, I fight to win".

However, her campaign manager Sir Peter Morrison provided disastrous advice. When Thatcher consulted Cabinet colleagues individually, almost all delivered the same message: they would support her, but she would lose.

Faced with this reality, Thatcher withdrew her candidacy on 22 November, throwing her support behind John Major. In the second ballot on 27 November, Major secured 185 votes against Heseltine's 131 and Douglas Hurd's 56, prompting both challengers to withdraw immediately.

Why did Conservative MPs remove a leader who had delivered three consecutive election victories? The simplest explanation is electoral calculation. Labour had led opinion polls since May 1989, enjoying a 21-point margin after Howe's resignation. Many MPs believed changing leader represented their only chance of avoiding defeat in the next election.

Thatcher had achieved remarkable successes: seeing off Labour leaders, taming trade unions, crushing inflation, revolutionising the economy, and helping end the Cold War alongside like-minded US presidents. Yet not all had prospered - inequality widened and unemployment remained stubbornly high.

As she departed Downing Street for the final time, Thatcher declared: "We're leaving after 11 and a half wonderful years, and we're very happy that we leave the United Kingdom in a very, very much better state than when we came here."

Her husband Denis had tried unsuccessfully to persuade her to step down in 1989 after a decade in power. In truth, she would likely never have left willingly. As with all transformative leaders, there would always be more work to do. Her removal required Conservative MPs to act before the electorate could.