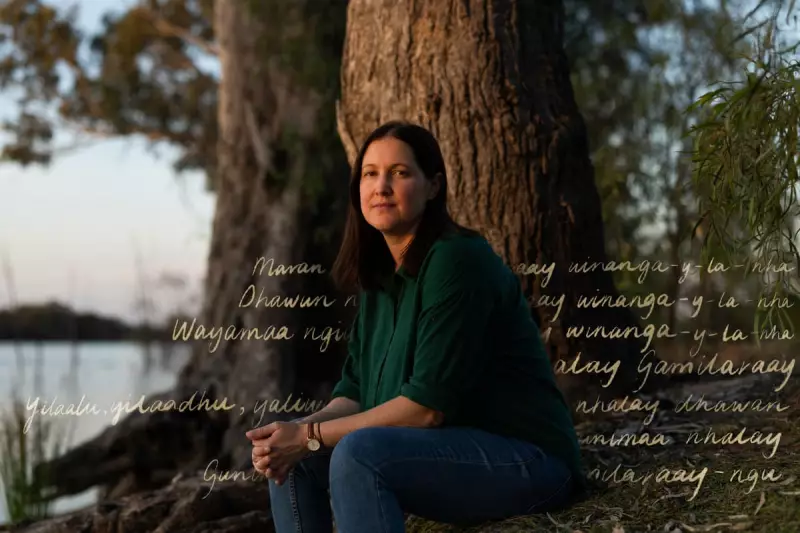

After thirty-four years, journalist Ella Archibald-Binge finally made the pilgrimage to her grandfather's ancestral lands around Toomelah in north-western New South Wales. Guided by Gomeroi elder Carl McGrady, she embarked on a profound journey to understand how language, country, and culture intertwine for First Nations people reclaiming their heritage.

The Sacred Waters of Boobera Lagoon

The journey began along a rugged bush track that suddenly revealed what Uncle Carl describes as "the east coast Uluru" - Boobera Lagoon. This vast seven-kilometre waterhole, fed by artesian springs beneath the dry plains, has served as a sacred meeting place for Aboriginal people for millennia.

"For mob who come home for the first time, I say go to Boobera and jump in the water, then you know you're home," Uncle Carl explained to Ella on that scorching spring morning. The traditional owners deliberately keep the access difficult and unmarked, preferring to protect this spiritually significant site.

Standing at the water's edge, Uncle Carl shared the creation story of Garriya, the rainbow serpent who still rests in the lagoon according to Gomeroi belief. The tale of the brave warrior Dhulala confronting the serpent explains both the landscape's formation and the cultural prohibition against visiting the waterhole after dark.

Reconnecting with Ancestral Lands

Ella, a proud Kamilaroi descendant raised just three hours from this country, had never visited the place where her pop's story began. Her grandfather, Neville Binge, had shared stories of mission life in his later years, but like many of his generation, never spoke his native language.

Their first stop was Old Toomelah (Dhumalaa), where Ella's great-grandparents lived from approximately 1926 to 1938. All that remains are house stumps, a clearing where ceremonies once took place, and a cemetery containing clusters of small headstones marking babies lost to an unknown disease that swept through the mission.

Uncle Carl pointed out native plants and their traditional uses - saltbush for eating, eurah tree as "blackfella's penicillin," warrigal greens, and the sacred bambul tree said to embody Garriya's mother-in-law. "Back when things were being created, everything had spirits: rocks, trees, people," he explained.

Reviving a Sleeping Language

The journey also explored the ongoing revival of the Gamilaraay language, which was systematically suppressed during the mission era under the NSW Aborigines Protection Act. Adults needed permission to work in town, houses were routinely inspected, and speaking language was strictly forbidden.

"The fear of that far outweighed the hunger and need to want to pass on the culture," Uncle Carl recalled. "Unfortunately here we are a hundred years later... trying to resurrect it."

He described how mission residents developed "mission English" - using English words arranged according to Gomeroi grammar as a subtle form of resistance. It wasn't until the 1990s, when Uncle Carl began teaching at a local school, that the serious work of language revival began through conversations with elders by the river.

Those initial scribblings evolved into books and eventually the school's first Gamilaraay language course. Today, more than ninety Gamilaraay speakers exist, ranking it among the top ten Indigenous languages being revived nationally according to a 2019 AIATSIS survey.

As Ella prepared to leave, she returned alone to Boobera Lagoon, stepping into the milky water as Uncle Carl had suggested. Feeling the grainy mud between her toes, a gust of wind sent down a shower of leaves - a sensation she later identified with the Gamilaraay word yarragaa, meaning "the warm wind that kisses the trees to make them bloom."

Though she doesn't yet know her language fully, Ella concluded that tasting the saltbush and hearing the birds descend on the lagoon at sunset felt like the right place to begin reconnecting with her Gomeroi heritage.