Scientific analysis using advanced infrared technology has uncovered a remarkable secret hidden beneath the layers of paint in a famous portrait of Anne Boleyn, revealing what historians believe was a deliberate attempt to debunk witchcraft accusations against Henry VIII's ill-fated wife.

Infrared Revelation at Hever Castle

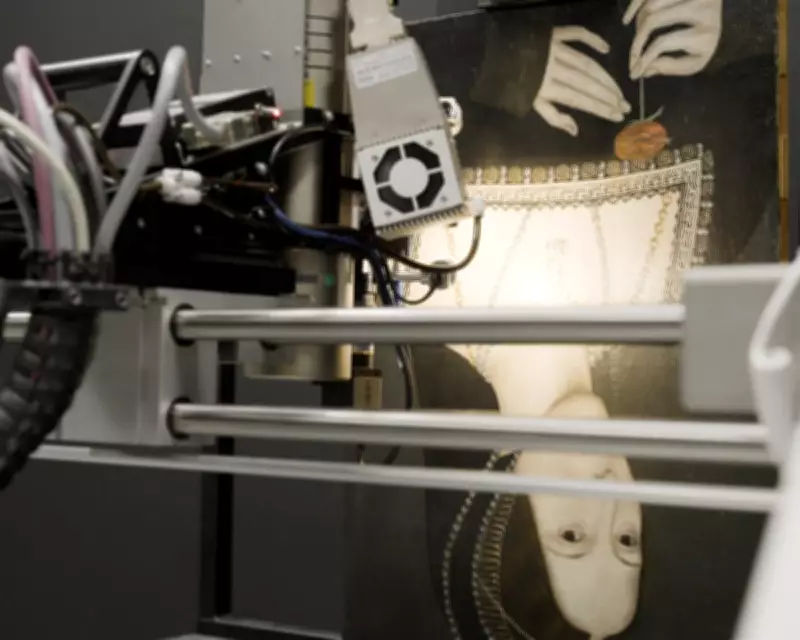

The painting, known as the Hever "Rose" portrait for its depiction of Anne holding a red rose, has been subjected to detailed scientific examination at Hever Castle in Kent, Anne's childhood home. The infrared reflectography has revealed a dramatic underdrawing that shows the artist's original intentions before creating the final composition.

A Visual Rebuttal to Witchcraft Claims

Historians examining the newly discovered evidence believe the portrait represents a "visual rebuttal" to persistent rumours that Anne Boleyn possessed a sixth finger on her right hand, a physical characteristic traditionally associated with witchcraft in Tudor England. The underdrawing shows a discarded triangular form beneath Anne's right arm, indicating the precise moment the artist decided to depart from the established pattern and instead clearly display her hands with five visible fingers.

Dr Owen Emmerson, assistant curator at Hever Castle, explained the significance of this discovery: "By clearly displaying five digits on each hand, the portrait acts as a visual rebuttal to hostile rumours and as a defence of Anne Boleyn – and, by extension, of her daughter Elizabeth's legitimacy."

Political Context During Elizabeth I's Reign

Tree-ring analysis has dated the oak panel to approximately 1583, placing its creation firmly within the reign of Elizabeth I, Anne's daughter. This timing coincides with a period of intense political and religious anxiety in England, when Elizabeth's legitimacy was frequently challenged by Catholic opponents.

Kate McCaffrey, another assistant curator at Hever, emphasised the political significance: "This is very strong evidence of a visual rebuttal of a very specific myth of witchcraft and six fingers. The scientific analysis extends this to a very specific political moment in time. It's Elizabeth's way of not only reclaiming her own legitimacy and lineage, but also restoring the legitimacy of her mother."

Historical Patterns and Artistic Adaptation

In the sixteenth century, royal portraits were typically created using established "patterns" drawn from brief life sittings, which were then circulated between workshops as approved likenesses. The Hever portrait initially used the so-called "B" pattern, which generally focused on Anne's head and shoulders, before being adapted for political purposes.

The analysis supports theories proposed by historian Helene Harrison in her 2025 book, The Many Faces of Anne Boleyn, which suggested that Anne's prominently displayed hands in the portrait were intended to counter claims made by Nicholas Sanders, a sixteenth-century Catholic activist who wrote that Anne had "on her right hand six fingers" as part of his campaign to undermine Elizabeth I's legitimacy.

Scientific Methodology and Exhibition

The dendrochronological analysis was conducted by independent specialist Ian Tyers, while the infrared reflectography and material analysis were performed at the Hamilton Kerr Institute at the University of Cambridge. These scientific techniques have established that the Hever portrait is the earliest scientifically dated panel portrait of Anne Boleyn currently known.

The portrait will feature prominently in a forthcoming exhibition at Hever Castle titled Capturing a Queen: The Image of Anne Boleyn, which will explore how Anne's image was "created, deliberately altered and politically deployed" throughout history. The exhibition opens on 11 February and will run until 2 January 2027.

Anne Boleyn's Enduring Legacy

Anne Boleyn's historical significance extends far beyond her tragic execution in 1536. Her marriage to Henry VIII precipitated England's break with the Catholic Church and initiated the English Reformation. Following her execution for treason and adultery – charges she consistently denied – Henry VIII systematically removed all traces of her from royal palaces, and no portrait painted during her lifetime is believed to have survived.

Contemporary accounts of Anne's appearance varied considerably. While the Venetian ambassador Francesco Sanuto described her as "not one of the handsomest women in the world", the German humanist Simon Grynaeus found her "good-looking". According to McCaffrey, "Her appeal lay in her intelligence, confidence and charisma. That is what caught Henry's eye and heart."

The discovery of the underdrawing provides fascinating new insights into how Anne Boleyn's image was manipulated and redeployed for political purposes during her daughter's reign, offering a tangible connection to the complex power struggles and religious tensions of Tudor England.