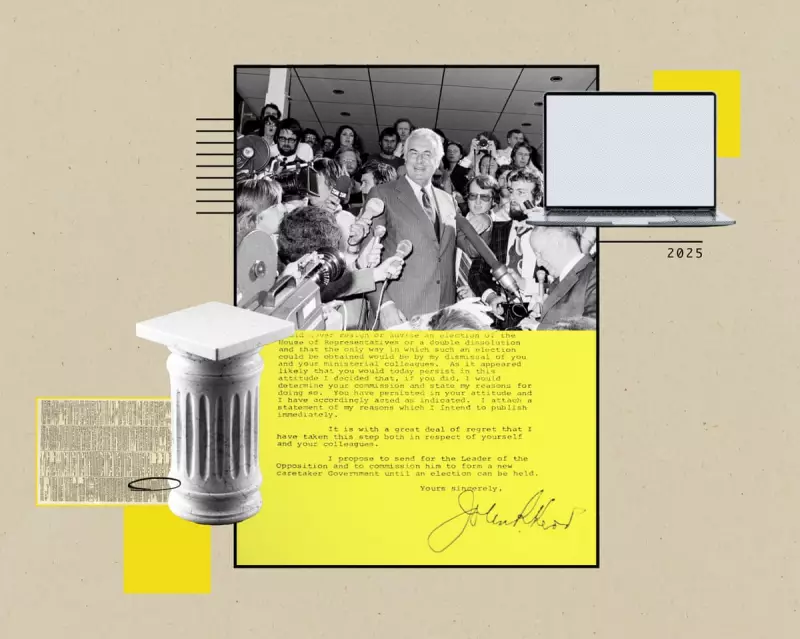

Fifty years ago, Australian democracy faced its most severe test in living memory. The dismissal of the democratically elected Whitlam government by Governor-General Sir John Kerr in November 1975 sent shockwaves across the nation, revealing the fragile nature of the country's political institutions.

The Constitutional Crisis That Shook a Nation

Few Australians in 1975 believed the vice-regal dismissal of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam represented normal political business. The unprecedented move by Sir John Kerr created widespread shock and anger among the populace, with Whitlam famously urging his supporters to "maintain your rage."

While much has been written about the principal actors—including Whitlam, opposition leader Malcolm Fraser, and Kerr himself—less attention has been paid to what historians call "the dismissal from below," examining events through the eyes of ordinary citizens.

Threat of Widespread Civil Unrest

The potential for significant public disorder was very real. With trade union membership at approximately 55% of workers in the mid-1970s (compared to just 12.5% today), the threat of a general strike loomed large.

Sir John Kerr himself recognised the danger, writing to the palace shortly after initial protests: "As the money runs out many problems will arise and the reaction of the trade unions has to be considered. There are threats of protest, strikes and industrial 'war'."

Within political circles, fears ran high. Liberal MP Ian Macphee warned that if the Coalition won an election stemming from the crisis, they would face "the outright hostility of nearly 50 per cent of the electorate." Former Prime Minister John Gorton feared the situation might lead to "riots and strikes ... fighting in the streets."

From Violent Incidents to Peaceful Protest

While the feared general strike never materialised—partly due to Australian Council of Trade Unions president Bob Hawke opting for moderation—the period did witness violent episodes.

A letter bomb exploded in the building containing Queensland Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen's office, seriously injuring two staff members. Additional letter bombs were sent to both Fraser and Kerr, though these caused no damage. Open fights broke out between Whitlam and Fraser supporters, and there were occasional clashes with police.

Nevertheless, the response from below was predominantly peaceful. Hundreds of thousands of workers walked off the job in protest, but you were more likely to encounter songs, chants, and satirical street plays mocking Kerr and Fraser than outright violence.

Legacy of the Dismissal

The events of 1975 foreshadowed the political order that would emerge in the 1980s, embodied by Bob Hawke, who would become Labor leader and later prime minister. Hawke's moderate approach, which contrasted with Whitlam's fiery rhetoric, resonated with the Australian public and laid groundwork for his eventual electoral success.

Time has been kind to Whitlam's legacy, with his government's policy achievements now overshadowing memories of the constitutional crisis. Yet for a period in 1975, Australian democracy appeared dangerously fragile.

The system ultimately proved robust, thanks in large part to ordinary Australians who creatively agitated for their democratic institutions. In today's world, where democracy often appears in decline, we can learn much from the vigilance of those who rallied as spring turned to summer fifty years ago.