Can Ugly Thoughts Make You Ugly? The Complex Link Between Inner and Outer Beauty

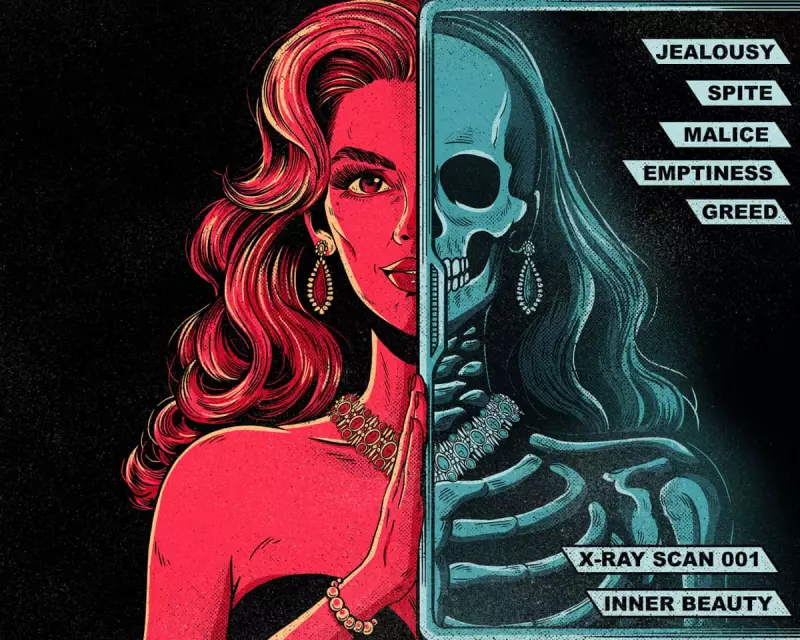

Our perception of a person's physical beauty is often deeply coloured by our views on their behaviour. But what if we could completely divorce the concepts of inner and outer beauty? This question lies at the heart of a fascinating debate about how we judge appearances based on moral character.

The Age-Old Belief: Soul Shaping the Body

There's a common saying that we end up with the face we deserve. The idea suggests that hurtful or spiteful thoughts can tense and harden our facial features over time. Similarly, neglecting personal needs might show visible signs on one's face. However, this perspective raises a critical contradiction: if the soul shapes the body, then inner beauty should be visible, yet proponents also claim that no wrinkle can hide such beauty.

This leads to a thought-provoking experiment. How can we visually distinguish wrinkles from ordinary ageing in a good-natured person versus those from a spiteful individual? The truth is, we cannot, because bodies and souls do not interact in this simplistic way. Despite this, these beliefs remain widely held and persistently influential in society.

Modern Examples: Public Reactions and Cultural Narratives

Consider the public reaction to recent portraits of political figures, such as those from the Trump administration in Vanity Fair. Comedian Lisandra Vázquez commented on press secretary Karoline Leavitt's fine lines, suggesting that evil causes one to age poorly, a post that garnered significant engagement online. Similarly, images of chief of staff Susie Wiles sparked remarks about lying affecting skin or hate ageing people horribly, with jokes about physical features like thin lips.

In contrast, think of the pivotal scene in the 2023 film Barbie, where a 91-year-old woman is called beautiful by Barbie. Director Greta Gerwig described this moment as the heart of the movie, and fans echoed this sentiment, praising the beauty seen in women who have lived full lives. These examples highlight how our perception of physical beauty is heavily influenced by our ethical judgments of behaviour.

Why We Confuse Ethics with Aesthetics

Our brains tend to collapse ethical judgments into aesthetic ones because humans are visual creatures, eager to make abstract thoughts visible. When you see wrinkles and associate them with evil, it's not because wrinkles signal moral failing; it's because you believe the person's actions do. Conversely, warmth from an old lady can make her appear beautiful, not due to wrinkles indicating virtue, but because her behaviour evokes positive feelings.

The false link between inner goodness and outer beauty has deep historical roots. In ancient Greece, the word kalos was used for both beauty and goodness. During the 18th century, pseudosciences like phrenology and physiognomy claimed facial features reflected character, ideas later weaponised by racists and eugenicists. Although discredited, this framework persists in Western culture, as explored in works like Heather Widdows' Perfect Me: Beauty As an Ethical Ideal.

Profitable Myths and Language Solutions

This association is also lucrative for cosmetic companies, which market inner beauty through external consumption, as noted by Tressie McMillan Cottom in Thick & Other Essays. To find an inspiring solution, we might consider completely separating inner and outer beauty, starting with language. Today, beauty serves as a catch-all term for various ideas, from natural beauty to physical appearance and emotional states.

Using the same word for disparate concepts, such as altruistic acts and cosmetic procedures, creates confusion. Philosophers like Immanuel Kant argued that true beauty must be disinterested, appreciated for its own sake without personal benefit. Iris Murdoch described it as an occasion for unselfing. Thus, what the beauty industry sells is often not beauty but appearance, cosmetics, or hygiene.

Redefining Terms for Clarity

If a person's appearance or spirit incites desire, that's attractiveness. When your face shows signs of neglected needs, it relates to health—factors like dehydration or stress affecting skin, but not moral desert. Good people experience stress that forms wrinkles, while bad people may maintain flawless skin through meditation or healthcare access.

Everyone deserves health access, but no one has a moral obligation to look healthy. As for inner beauty contributing to the greater good, it might be better termed simply as goodness. Focusing on this won't change your face, but as the saying goes, no wrinkle can hide it either, offering a positive perspective on ageing and character.