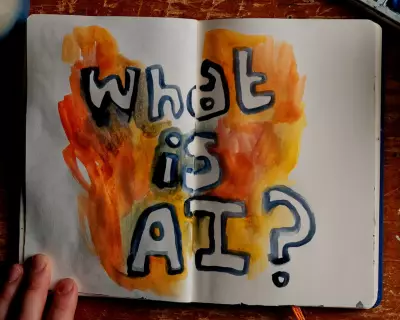

When excruciating pain left Daisy Lafarge unable to sit upright or concentrate on reading and writing, the award-winning poet and novelist turned to a different creative outlet. Lying on her living room floor in Glasgow, suffering from a severe injury and worsening symptoms of her connective tissue disorder, she began creating impressionistic paintings using whatever materials she had within reach.

Creating Art Amidst Chronic Pain

"Making the paintings was a way of coexisting with pain," explains the 34-year-old artist. "I was on my living room floor in agony for a few hours, but I wanted to get something out of that time. I've always been fascinated by artists and writers who turn limitations into formal constraints. I see the paintings as my attempt at that."

Lafarge, who has Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, used basic materials including inexpensive paper, paints, and brushes. She also incorporated kinesiology tape into her artwork - the same adhesive tape she uses to support her joints and ligaments. The tape must be cut in specific ways, leaving distinctive butterfly-shaped remnants that Lafarge repurposed as decorative elements in her watercolours.

From Floor to Gallery

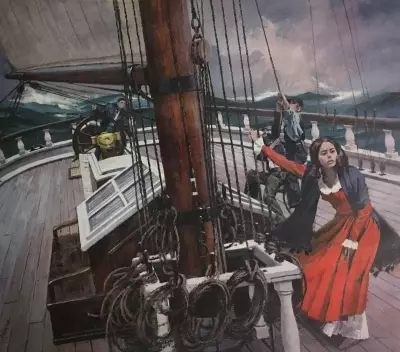

The resulting paintings depict her immediate surroundings - her cat Uisce, her boyfriend's PlayStation controller - alongside more unsettling imagery of enclosed gardens and decaying flowers. These works will be accompanied by a poem cycle inspired by William Blake's The Sick Rose and the 13th-century text The Romance of the Rose, exploring pain as an "intoxicating, sometimes quite violent" lover through allegorical storytelling.

This month, Lafarge's paintings and poetry will feature in We Contain Multitudes at Dundee Contemporary Arts Centre, an exhibition showcasing four artists with disabilities. The show also includes Jo Longhurst, whose latest project draws inspiration from resilient bindweed; Andrew Gannon, who creates work based on casts of his left arm; and Nnena Kalu, whose textured, cocoon-like sculptures and drawings earned her the 2025 Turner prize - marking the first time the award has gone to an artist with learning disabilities.

Beyond Token Representation

"I think it's great that Nnena won the Turner," Lafarge comments. "I love the way her work takes up space, its undaunted physicality. I hope it leads to more inclusion of disabled artists. But I don't want to be naively optimistic."

She continues with a sobering perspective: "I just find it so hard to disentangle from the fact that disabled artists are disabled people. So is it really a turning point, unless disabled people can afford to be alive in this country? That comes down to structural issues: are they able to heat their own homes, pay their carers and access very basic things? It's been an incredibly bleak time from that perspective. A celebratory representation without actual material change is kind of meaningless."

The Bureaucratic Burden

For many disabled individuals, managing complex conditions and chronic pain is compounded by bureaucratic obstacles when seeking treatment and support. Lafarge has never been able to consult an Ehlers-Danlos specialist through the NHS, as none exist in Scotland. She created many of her paintings while waiting on lengthy call queues for adult disability payment, Scotland's equivalent of personal independence payment.

"When you're trying to get support from these institutions, which are punitive in various ways, that can take a lot out of you as well," she explains. "Those processes can be incredibly difficult."

Lafarge describes last year's welfare cuts implemented by Labour as a "huge assault" on disability rights, though she acknowledges progress in certain areas. The increasing use of access documents - where art workers specify required adjustments like wheelchair ramps or regular breaks - represents one positive development. "Most of the time now, thankfully, they'll come back and say, 'Yes.' But sometimes they'll say, 'No, we can't.'"

Challenging Preconceptions

Lafarge hopes exhibitions like We Contain Multitudes can challenge assumptions about disabled artists and, by extension, disabled people generally. The four featured artists represent diverse conditions and approach disability through markedly different artistic lenses.

"One great thing to come out of this show would be for people to say, 'I wouldn't have assumed the artist who made that is disabled' - because it shouldn't have to be obvious from the content," she suggests.

She emphasises that her paintings and poems should resonate with audiences regardless of physical ability. "You don't have to be disabled to engage with this work. That's a diminishing of it."

Identity and Inclusivity

Lafarge has reflected deeply on identity since her diagnosis. "When I was first diagnosed, I really didn't want to over-identify with it and say, 'I am a writer with this condition.' I just wanted to be a writer, or I wanted to be an artist. There's this pressure to outwardly identify with something you might feel personally ambivalent about. That's frustrating."

She argues that disability shouldn't be viewed as separate from everyday experience or as a distinct category of personhood. "People don't realise that this work is about them as well," Lafarge observes. "Many people will, either through old age or injury or illness, come to know something of that experience. We're one in four people. It's not unusual. This implicates all of us."

We Contain Multitudes runs at Dundee Contemporary Arts from 7 February to 26 April. Daisy Lafarge's most recent book, Lovebug, is published by Peninsula Press.