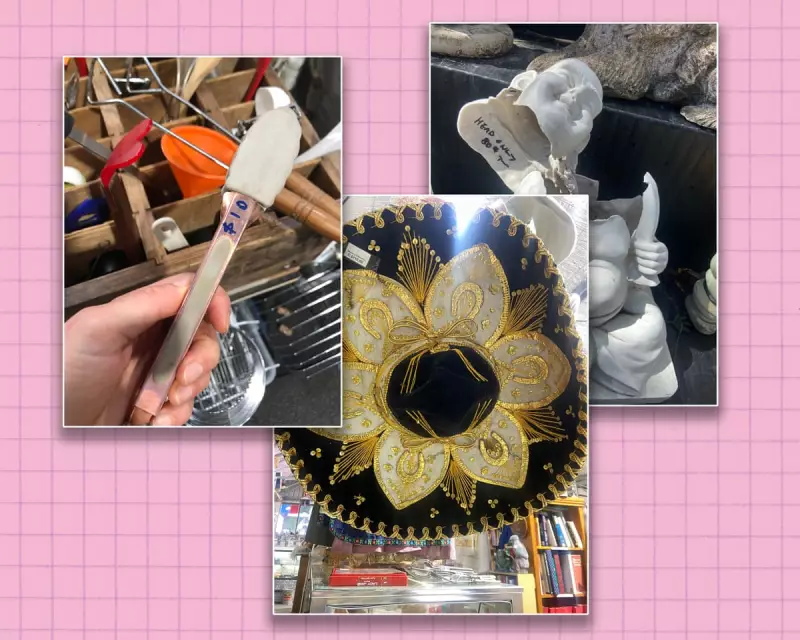

Walking through a tip shop recently, I had a moment of genuine disbelief. While searching for a simple whisk I expected to cost no more than £2, my eyes fell upon a small pair of used kitchen tongs. The price, scrawled directly onto the metal with a permanent marker, read £10.

I immediately photographed my find and shared it with a group of dedicated op-shopping friends. Their reactions were swift and unanimous. One quipped, "Tell 'em they're dreamin'!" The sentiment was understandable – a quick online check revealed an identical, brand-new pair from a popular retailer for just £1.75.

The Rising Cost of Secondhand Finds

This experience is far from unique. Across the UK, stories are emerging of charity shop and tip shop prices that sometimes exceed the cost of buying the same items new. One friend recounted spotting a Spider-Man toy priced at £15 in an op shop, only to find it later in a supermarket for £10. Others report seeing clothing from budget brands like Anko carrying higher secondhand price tags than their original retail value.

The phenomenon extends to items deemed "vintage." While some are genuine treasures, others test the limits of value. Is a rusty 'Willow' bakeware cupcake tin truly worth £12 instead of £2 just because similar pieces are sought after online? And what are the odds that a grimy, cracked German-made Kakuro truck, priced at a bold £27.50, will find a buyer in a local tip shop?

The pricing strategies can sometimes border on the absurd. I once saw a Lego box priced at a tempting £4, only to discover the tag read "box only." Another friend attempted to buy some old, urine-stained carpet to use as a weed mat, but the shop refused to budge from its £40 asking price.

Balancing Act: The Economics of Charity Retail

While these are extreme examples, they highlight a growing tension in the world of secondhand retail. For op shops, setting prices is a delicate balancing act. Price items too high, and they risk alienating their core customer base, particularly those on tight budgets. Price them too low, and they struggle to cover operational costs and support their charitable missions.

Jaharn Quinn, an experienced thrifter, has observed a noticeable increase in secondhand prices over the last five years. "The cost of secondhand items – furniture especially – is often close to the retail price," she notes. While she worries that some shops may be inadvertently pricing out those in genuine need, she remains supportive of their overall mission. "They are doing so much to help local communities and I value all the hard work they do, even if I don't agree with their pricing."

Ryan Collins, Head of Impact and Research at Planet Ark, explains the broader implications. Overpricing can deter people from buying secondhand, potentially driving them towards new products and increasing consumption. Conversely, underpricing can devalue the concept of reuse and make it financially unsustainable for these enterprises to continue their vital work.

The Value Beyond the Price Tag

Collins suggests that when consumers encounter higher-than-expected prices, it might be because an item is of superior quality and offers better long-term value. But even when this isn't the case, he emphasises a crucial point: "You're not just buying a product, you're investing in a system that reduces waste and benefits the community."

This perspective is echoed by Rena Dare, a director at the Recovery Circular Hub, home to Australia's longest-running tip shop. She argues that environmental conservation comes with real costs. Her locally-owned business operates without tax breaks and pays fair wages to a skilled team. Prices are set using detailed guides and are non-negotiable.

With over 35 years of experience, Dare has an almost clairvoyant sense of what will sell and what will end up in landfill by the weekend. Her team even refuses to resell certain items, like some fast fashion, which can release harmful microplastics. "Some things don't deserve to be put back into circulation because they shouldn't be made in the first place," she states.

Despite the occasional pricing shock, the thrill of the hunt remains a major draw. Part of the charm of secondhand shopping is its inherent unpredictability. And prices aren't always set in stone; many seasoned op-shoppers have stories of cashiers spontaneously slashing a price after declaring it "far too much." One friend, ready to pay £80 for an old oil painting, was charged just £8 after the staff member decided "That's better!"

Ultimately, the landscape of secondhand shopping is evolving. As we navigate the delicate balance between affordability, sustainability, and supporting charitable causes, one thing is clear: the conversation around the true value of our pre-loved possessions is more relevant than ever.