Britain's high streets are caught in a vicious cycle of decline that is having profound political consequences across the nation. New analysis reveals that the visible deterioration of local shopping areas is directly fueling support for far-right political movements, creating a dangerous feedback loop between economic decay and political radicalisation.

The Visible Face of National Decline

From northern England to coastal towns and the Midlands, boarded-up shops have become an increasingly common sight. Traditional banks and department stores have been replaced by vape shops, barbers, and bookmakers, while shoplifting has reached record highs and public frustration continues to mount. This physical decay is creating fertile ground for political movements that promise radical change.

Political Consequences of Retail Collapse

Research demonstrates a clear correlation between struggling high streets and political outcomes. Support for Nigel Farage's Reform UK is significantly higher in areas experiencing the most severe increases in persistent vacancy rates. In 2024 alone, nearly 13,000 shops closed permanently across the UK - equivalent to about 37 closures every single day.

Professor Thiemo Fetzer from the University of Warwick, whose previous research has linked austerity and Brexit to social outcomes, has found that locations with the highest rates of shop closures in England and Wales are more likely to back right-wing populist parties. "It has channelled people's anger at the structural change around them," Fetzer explains. "They don't always personally perceive things to be negative for them. They say: 'I'm doing fine.' But they see and feel their community around them eroding."

The Psychology of Community Erosion

In-depth polling by YouGov and researchers at Faster Horses reveals that 62% of voters considering backing Reform believe their local area is in decline. The emotional impact is profound, with one focus group participant telling researchers: "It's just soul destroying to watch your local area turn to shit." For many Britons, this local decay reflects what they perceive as national decline, with the country having "gone to the dogs" despite promises from successive Conservative and Labour governments.

Multiple Factors Driving the Crisis

The decline of Britain's high streets stems from a complex interplay of factors. The digital revolution has transformed retail fundamentally, with online spending rocketing from less than 3% of total retail sales in 2006 to more than 25% today. This shift was accelerated dramatically by the Covid pandemic, creating permanent changes in consumer behaviour.

Retailers face multiple pressures including weaker consumer demand during the cost of living crisis, flatlining real wages throughout the 2010s, and inflation reaching 40-year highs. Many consumers are prioritising spending on experiences over physical goods, with some experts believing Britain reached "peak stuff" years ago.

Structural Disadvantages and Policy Failures

The business rates system creates a significant disadvantage for bricks-and-mortar shops compared to online retailers. This tax, based on commercial property values, makes maintaining a chain of high street shops more expensive than operating a warehouse on the outskirts of town. Despite Labour's pre-election promise to replace the system in England, changes have been limited to what Chancellor Rachel Reeves described as the "lowest tax rates since 1991" for the existing framework.

Additional pressures include elevated inflation, interest rates, tax increases, government regulations, rising minimum wage requirements, and sharp increases in rents and utility costs. Hospitality businesses warn that rising bills are putting high street pubs, cafes, and restaurants at particular risk.

The Social Dimension of Decline

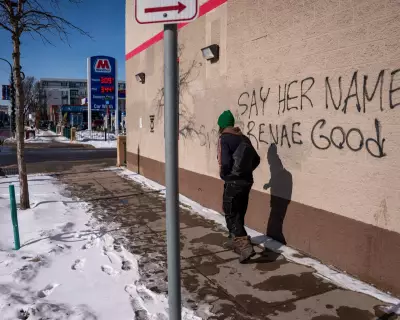

Beyond economic factors, underinvestment in transport, policing, healthcare, and social services has contributed to the high street crisis. Homelessness has risen significantly, while shoplifting offences increased by 13% to more than half a million offences in the year to June 2025.

Fetzer believes these factors, combined with the rise of online shopping, have fuelled social isolation and fear of others, further discouraging high street visits. "People have lost their ability to speak to one another," he observes, describing a "non-linear tipping point where you cascade into oblivion" that affects midsize towns particularly severely.

Self-Reinforcing Patterns and Partial Solutions

Some of the decline is self-perpetuating. Almost half of Britons do not visit their high street or shopping area at least once a week, with the top barriers being self-reinforcing: not enough interesting shops and too many empty ones.

Some areas buck the trend, typically where there is a higher concentration of independent retail, hospitality, and tourism to attract visitors. However, big cities and affluent areas find this easier to sustain, adding to perceptions of Britain as an increasingly divided nation.

Government Responses and Future Challenges

The Labour government has announced £5 billion of "Pride in Place" funding for communities to invest in local priorities, including buying community spaces and revamping high streets. Ministers have also established a taskforce to tackle problematic high street stores and a licensing scheme to ensure only legitimate shops can legally sell tobacco and vapes.

Despite these measures, the danger for Prime Minister Keir Starmer is the depth and complexity of the economic challenge facing high streets. With retail accounting for just 5% of the UK economy and less than a tenth of employment, its visible position gives it outsized influence on public perception. Any meaningful turnaround before the crucial set of May local elections appears increasingly difficult to achieve.