When a supporter of Nigel Farage recently told Justice Secretary David Lammy to "go home to the Caribbean," it echoed a familiar, ugly refrain in British politics. But for many, including those with Windrush heritage, the concept of a single "home" is a complex fiction, starkly revealed by modern genealogy.

A Personal Journey Through DNA and Belonging

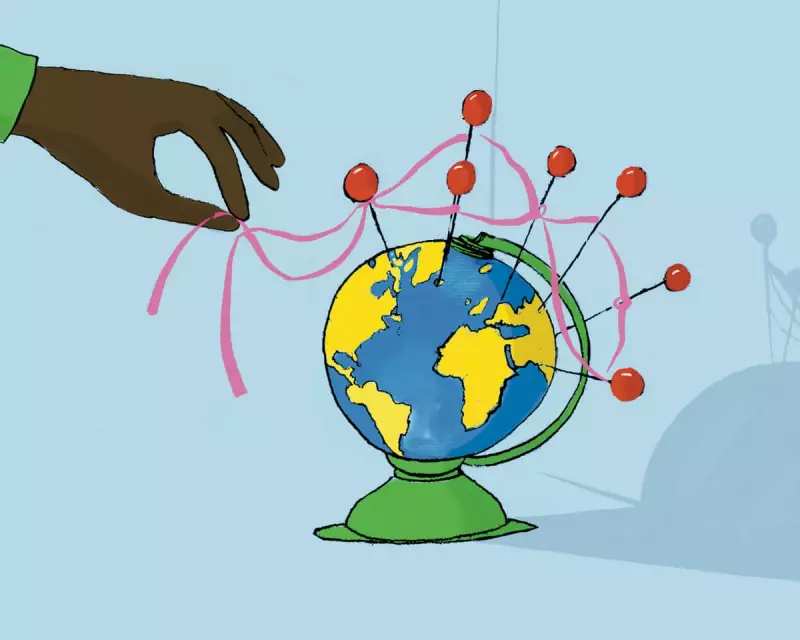

Hugh Muir, a journalist and executive editor, decided to explore his own ancestry with a DNA test. The results were illuminating and defied simple categorisation. Through his mother's line, the test revealed genetic traces from Benin and Togo, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Nigeria, Mali, north-east Scotland, and even Iceland. From his father, he inherited links to Nigeria, Devon and Somerset, Cameroon, Mali, Senegal, Panama, Costa Rica, and the Netherlands.

This mosaic of origins, connecting him to well over a dozen countries across continents, powerfully challenges the populist notion that identity is a neat parcel with one return address. "I am not a citizen of nowhere," Muir reflects, "but through history, politics, cruelty and happenstance, a creature from almost everywhere."

The Political Backdrop: A Surge in Nativist Rhetoric

This personal exploration comes against a disturbing national backdrop. The year 2025 has seen what Muir describes as bigotry in frontline politics taking "off its training wheels." He cites several key events: the violent besieging of asylum seeker hotels condoned by some right-wing figures; the co-opting of the Union Jack and St George's flag as tools of intimidation; and serious allegations about Reform UK leader Nigel Farage's past conduct as a school bully.

Beyond the headlines, Muir recounts everyday bigotry experienced by friends and acquaintances: a black friend verbally assaulted in rural England; a student and his father told a pub was unsafe for "Pakis"; a black health worker feeling newly vulnerable in flag-draped villages. A study by the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) confirms a rise in people absorbing hard-right narratives.

Precarious Citizenship in Modern Britain

For British citizens from minority backgrounds, the sense of belonging is often tempered by legal vulnerability. Muir, the son of Windrush migrants who arrived in the 1950s, recalls the shock when the 1971 Immigration Act forced his parents to re-secure their status. That insecurity persists today.

Under the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002, the Home Secretary can strip citizenship without notice if it is deemed for the "public good." Research by the Runnymede Trust this year suggested 9 million people, largely those with dual nationality, are vulnerable, with minority citizens 12 times more at risk than white Britons. "You belong until, maybe, one day, you don't," Muir observes.

The command to "go home" is not just a slur but a logical absurdity for millions. For David Lammy, for Hugh Muir, and for countless others with multifaceted heritage, home is unequivocally Britain—but their roots, as DNA tests can show, are woven into a global tapestry. Muir argues that a conversation about belonging that starts from this truth of interconnectedness, rather than narrow nativism, would be a far more positive national endeavour. In a year of heightened division, it is a conversation urgently needed.