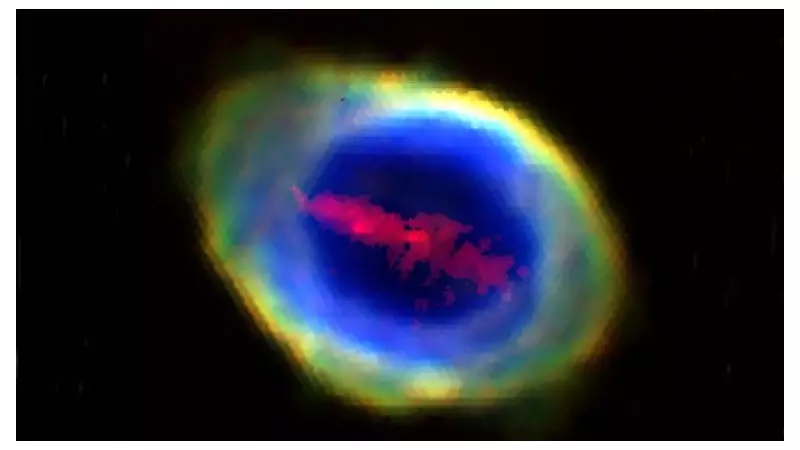

Astronomers have made a startling discovery within one of the night sky's most famous objects, uncovering a mysterious structure that may offer a glimpse into the distant future of our own planet.

A Familiar Nebula Reveals a New Secret

Using a powerful new instrument on the William Herschel Telescope in La Palma, researchers have spotted a peculiar cloud in the shape of a bar within the Ring Nebula, also known as Messier 57. This nebula, located roughly 2,600 light-years away in the constellation Lyra, is the glowing remnant of a sun-like star that died around 4,000 years ago.

The nebula formed when a star, about twice the mass of our Sun, exhausted its nuclear fuel, ballooned into a red giant, and then expelled its outer layers. What remains is a compact white dwarf, surrounded by an expanding shell of gas, primarily hydrogen and helium.

'This Is Weird': The Puzzling Iron Feature

The newly observed feature is a bar-shaped structure composed of iron atoms, stretching an immense 3.7 trillion miles (6 trillion kilometres) across the face of the nebula. The discovery was made with the WEAVE (WHT Enhanced Area Velocity Explorer) instrument.

"No other chemical element that we have detected seems to sit in this same bar. This is weird, frankly," said study co-author Professor Janet Drew of University College London. "Its importance lies in the simple fact that we have no ready explanation for it, yet."

Astronomer Roger Wesson of Cardiff University and UCL echoed the surprise, stating: "It is exciting to see that even a very familiar object - much studied over many decades - can throw up a new surprise when observed in a new way." The findings have been published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

A Chilling Parallel for Earth's Future

The most compelling theory for the iron bar's origin is that it represents the vaporised remains of a rocky planet. When the dying star shed its outer layers as a red giant, any nearby planets would have been utterly destroyed.

"A planet like the Earth would contain enough iron to form the bar, but how it would end up in a bar shape has no good explanation," admitted Mr Wesson. Professor Drew added that while a vaporised planet is a leading hypothesis, "there could be another way to make the feature that doesn't involve a planet."

This discovery provides a potential, sobering preview of what may await our solar system. In approximately five billion years, our Sun will undergo a similar transformation into a red giant, likely engulfing and destroying the inner planets, including Earth.

Studying nebulae like Messier 57, of which about 3,000 are known in our galaxy, allows scientists to examine the final stages of stellar evolution and understand the complex interactions between dying stars and their planetary systems.