The Viral Misquote: Gramsci's 'Time of Monsters'

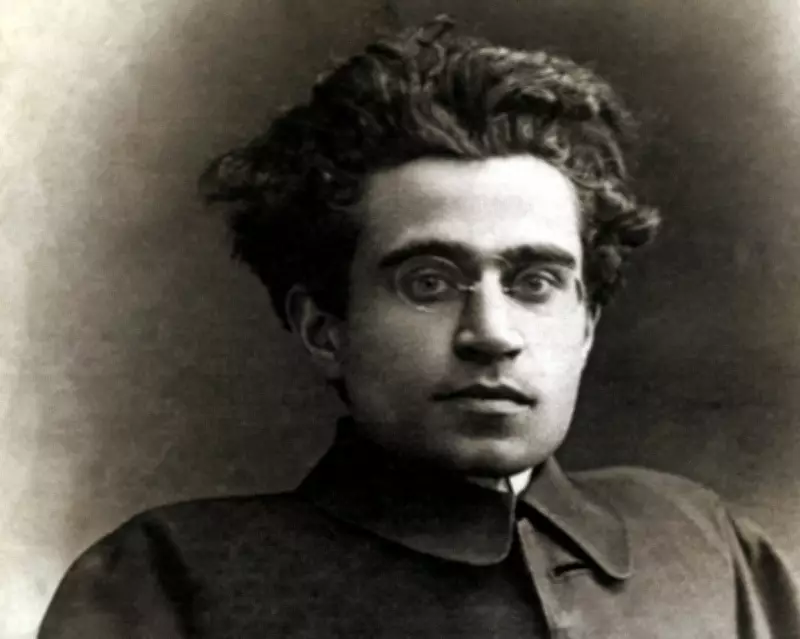

In an era where long-standing geopolitical certainties are rapidly dissolving, one particular quote has emerged as a popular shorthand for making sense of our turbulent times. "The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters" is widely attributed to Antonio Gramsci, the former leader of the Italian Communist Party. This evocative line has been cited by figures ranging from a right-wing Belgian prime minister to a left-wing British political leader, an Irish central banker, and even featured in the title of a recent BBC Reith lecture by author Rutger Bregman.

On social media platforms like Instagram, influencers solemnly warn their followers, "We can't let the monsters win," while on LinkedIn, business consultants post graphs illustrating the "Gramsci gap" and its implications for corporate strategy. The phrase powerfully encapsulates the sense of repulsion and disbelief many feel when confronted with contemporary news, whether it originates from the White House, the Epstein files, or the battlefields of Ukraine. It resonates with Francisco Goya's famous etching The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters as much as with modern pop culture references.

The Historical Reality: What Gramsci Actually Wrote

However, there is a significant problem with this widespread attribution: Antonio Gramsci never actually wrote or said those exact words, at least not in the concise, viral formulation that has captured the public imagination. After being imprisoned by the Italian fascist government in November 1926, Gramsci filled numerous notebooks with his thoughts on political theory, philosophy, and linguistics. In the original Italian, he wrote: "In questo interregno si verificano i fenomeni morbosi più svariati."

The most widely used English translation of the Prison Notebooks, produced by British academics Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith in 1971, renders this as: "In this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear." An alternative 1996 edition by Joseph Buttigieg, the late father of former US Transport Secretary Pete Buttigieg, speaks of morbid "phenomena" instead of "symptoms." Notably, neither translation includes any mention of "monsters."

The Origins of the Misattribution

The first recorded English use of the phrase "time of monsters" in connection with Gramsci appears in a 2010 article in the New Left Review by Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek, titled A Permanent Economic Emergency. In this context, the quote lends poetic weight to the challenges posed by the eurozone's banking crisis to the political left. When questioned about his decision to poetically refashion Gramsci's original words, Žižek claimed he could not recall the specifics but insisted he had taken the term from another source.

In fact, a French version of the phrase predates Žižek's popularization in English. As early as 1996, the phrase "dans cet interrègne surgissent les monstres" ("in this interregnum monsters arise") appeared in the pages of Le Monde. French economist and urbanist Gustave Massiah used a similar formulation, "Dans ce clair-obscur surgissent les monstres" ("in this twilight monsters arise"), in a 2003 essay. While the exact origin of Gramsci's association with monsters remains somewhat elusive, the phrase has undeniably taken on a life of its own in contemporary discourse.

Why Gramsci's Ideas Remain Relevant Today

Beyond the misquotation, there are compelling reasons why Antonio Gramsci's ideas continue to resonate powerfully in the modern era. Published posthumously in 1947, the Prison Notebooks were written during concentrated periods when the communist thinker was permitted pen and paper in his prison cell. "They distill a lot of things Gramsci had on his mind, so they are incredibly precise, at least for an Italian," noted Silvio Pons, president of Rome's Gramsci Institute.

The notebooks did not achieve truly global recognition until after the Cold War, with translations into more than 40 languages, but their central concepts have inspired activists for much longer. "When Gramsci wrote the Prison Notebooks, he was trying to make sense of why there hadn't been a socialist or communist revolution in Italy before the fascist takeover," explained Marzia Maccaferri, a political historian at Queen Mary University in London. "And the key concept to emerge from that thought process is his theory of hegemony: that the ruling class can rule not only through coercion, but also through the intersection of popular and high culture, through intellectual and civil society."

In continental Europe, this cultural turn influenced many of the student revolutionaries of 1968, while in Britain it provided a theoretical framework that Marxist sociologists like Stuart Hall applied to Thatcherism in the 1980s. However, as early as the 1970s, Gramsci's ideas were appropriated by Alain de Benoist, the chief thinker of France's Nouvelle Droite ("new right"). This attempt to center far-right politics on cultural rather than racial identities can be seen in former Trump strategist Steve Bannon's assertion that "all politics is downstream of culture," as well as in the rhetoric of key figures within the contemporary European far right.

The Danger of Simplifying Complex Thought

While the "time of monsters" quote has captured the imagination of today's politicians and thinkers, some scholars argue that it risks stripping Gramsci of the activist zeal that characterized his legacy for previous generations. "Monsters are something exceptional, an inverted miracle that comes out of nowhere with no real explanation," observed Peter Thomas, a historian of political thought and Gramsci expert at Brunel University London. "It's a metaphor that shuts off the possibility of trying to think through what is occurring. We get outraged or shocked at the monstrosity of these Trumpian figures, rather than trying to work out what produced it."

Before his imprisonment, Gramsci spent two formative years in revolutionary Russia, where he reportedly witnessed evidence that a new world, despite its struggles, could eventually be reborn. "It was almost inconceivable for him that whatever temporary setbacks he would have to suffer, we wouldn't eventually arrive at a victory," Thomas added. "We probably find it a little bit harder to think like that." This perspective highlights the danger of reducing Gramsci's complex, nuanced thought to a single, catchy phrase, however resonant it may be with contemporary anxieties.