Silence and Cry Review: Jancsó's Hypnotic 1968 Ballet of Hungarian Trauma

Miklós Jancsó's mysterious 1968 film Silence and Cry stands as a deeply strange somnambulist ballet, weaving together Hungary's political history with postwar Soviet realities in a mesmerising cinematic experience. This bizarre psychodrama, set after the fall of the 1919 Hungarian Soviet republic, creates an impenetrable psychological trauma with weird erotic overtones, reminiscent of an absurdist bad dream transcribed by Kafka himself.

A Vast Hungarian Stage of Political Allegory

The film unfolds on the vast Hungarian plain, where a desolate wind perpetually blows across a landscape that appears to extend Sahara-like to the far horizon in all directions. Jancsó transforms this space into a gigantic stage where characters perform their roles with haunting precision. Rather than conventional entrances and exits, figures gradually materialise from impossibly long distances, only to dwindle to vanishingly small dots as they depart.

Jancsó's distinctively sinuous camerawork glides and swoops elegantly around the action in a series of breathtaking long unbroken takes. This technical mastery creates a hypnotic quality that draws viewers into the film's unsettling atmosphere, where the brutality of anti-Communist powers in 1919 serves as both historical reflection and contemporary indictment.

Characters Trapped in a Miasma of Fear

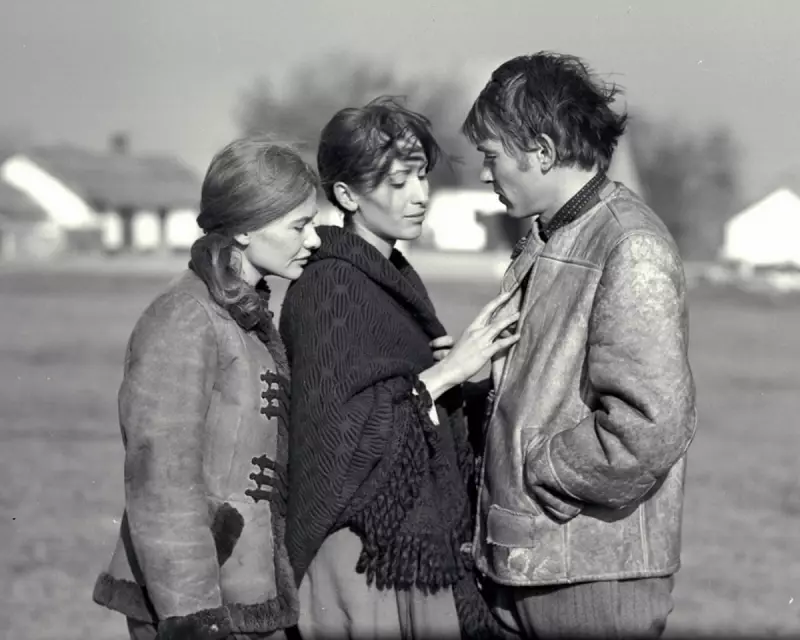

The narrative centres on István, played by András Kozák, a fugitive soldier hiding on a farm owned by two sisters, Teréz and Anna, portrayed by Mari Töröcsik and Andrea Drahota respectively. Driven perhaps mad by tension and isolation, the sisters are secretly poisoning Teréz's husband Károly, played by József Madaras, and his elderly mother.

An army officer named Kémeri, portrayed by Zoltán Latinovits, appears aware of István's presence but turns a blind eye in return for implied sexual favours from the women. This complex web of relationships unfolds against a backdrop where soldiers, led by a secret-police commandant in civilian garb, systematically menace the local population.

Rituals of Humiliation and Collective Punishment

The film's most powerful sequences involve bizarre rituals designed to humiliate and degrade. The commandant forces Károly and other civilians to inspect two dead bodies clearly killed by authorities, compelling them to touch the corpses and handle the dead men's personal effects including glasses, watches and wallets.

They must then hold up their hands to an official photographer, as if confirming their fingerprints on the relevant items and their supposed guilt. This ritual serves multiple purposes: it acquaints them intimately with fear, underlines their fellowship with the defeated dead, and demonstrates the arbitrary nature of authority in this traumatised landscape.

Houses are torn down as collective punishment, serving as grim lessons about what happens to those who refuse to cooperate. Wrongdoers, both military and civilian, endure prolonged standing in yards or are forced to perform humiliating "rabbit jumps." Through these scenes, Jancsó creates a pervasive miasma of fear and horror that settles over the entire landscape.

The Silence and The Cry as Political Statement

What emerges most powerfully from Silence and Cry is not conventional dramatic resolution but rather the overwhelming atmosphere of political oppression and psychological trauma. The film's central tension revolves around István's growing awareness of the women's homicidal activities and his moral dilemma about bringing them to justice without endangering himself.

Yet this narrative thread remains secondary to the film's larger meditation on power, complicity, and survival in oppressive political systems. Jancsó masterfully demonstrates how, in certain historical circumstances, silence and cry become indistinguishable responses to trauma.

Originally released in 1968, Silence and Cry continues to resonate as a powerful examination of political violence and psychological survival. The film's restoration and availability on Klassiki from 29 January offers contemporary audiences an opportunity to experience Jancsó's unique cinematic vision and Hungary's complex historical reckoning through art.