Fifty years after its initial release, Pier Paolo Pasolini's profoundly disturbing final film, Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, continues to cast a long shadow over cinema. To mark this grim anniversary, fellow filmmakers Abel Ferrara and Catherine Breillat have offered their powerful reflections on the work's brutal legacy and unsettling contemporary resonance.

A Film That Refuses to Be Forgotten

Premiering in 1975, just weeks after Pasolini's own murder, Salò transposed the Marquis de Sade's 18th-century fantasies to the fascist Republic of Salò in 1944 Italy. The film depicts a group of libertines systematically torturing and degrading a group of kidnapped teenagers. It was met with immediate outrage, banned in several countries, and remains one of the most controversial films ever made.

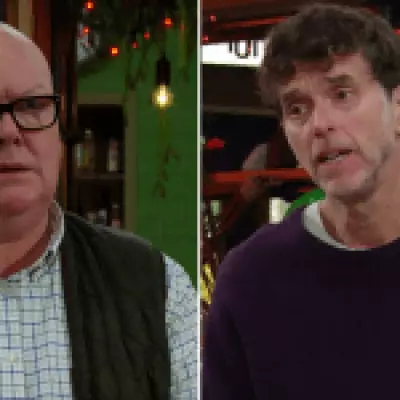

For director Abel Ferrara, known for his own gritty explorations of violence and morality in films like Bad Lieutenant, Salò is an uncompromising masterpiece. "It's not a movie you 'watch'," Ferrara stated. "It's an experience you survive. Pasolini wasn't giving us a narrative to enjoy; he was holding up a mirror to the absolute corruption of power, a mirror that hasn't cracked in fifty years."

Modern Echoes of a Historical Nightmare

Both Ferrara and French director Catherine Breillat, whose work often challenges sexual and social taboos, emphasised the film's frightening relevance today. Breillat argued that the film's depiction of institutionalised sadism and the commodification of bodies feels acutely modern.

"We live in an era of curated cruelty, of abstracted violence on screens," Breillat observed. "Salò removes the abstraction. It forces a physical, nauseating confrontation with the mechanics of power. When you see it now, you don't just think of 1944; you think of the atrocities we scroll past every day. Pasolini predicted the desensitisation of the image."

Ferrara echoed this sentiment, drawing a direct line from the film's fascist setting to current political climates. "He showed us the blueprint," Ferrara said. "The merging of erotic obsession with total political control, the language of purity used to justify filth—it’s a playbook some are still reading from."

An Enduring Cinematic Legacy

Despite—or perhaps because of—its infamy, Salò's influence has seeped into the fabric of provocative cinema. Its unflinching gaze has informed the work of directors from Michael Haneke to Lars von Trier. The film's 50th anniversary has prompted retrospectives and debates, ensuring it remains a critical touchstone.

The consensus from both Ferrara and Breillat is that Salò's power lies in its utter lack of catharsis. It offers no heroism, no escape, and no redemption for its victims or its audience. "It is the ultimate anti-spectacle," Breillat concluded. "It denies us the pleasure of looking, which is why we must look. That was Pasolini's final, furious lesson."

Half a century on, Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom stands not as a relic of past controversy but as a persistently alarming diagnosis of the darkest potentials of human society, a diagnosis that leading filmmakers confirm is as urgent now as it was in 1975.