In a decisive shift away from the clean, sparse aesthetic that has dominated interior design for years, a growing movement is embracing the emotional clutter of personal history. Writer Eleanor Burnard declares herself at the forefront of this trend, proudly filling her home with nostalgic knick-knacks that she says make it ‘impossible to be sad’.

The Rise of Sentimental Maximalism

Burnard describes her style as ‘sentimental maximalism’, a conscious rejection of minimalism in favour of objects brimming with memory. Her apartment is a testament to this philosophy, housing everything from faded stuffed toys and old birthday cards to a cherished One Direction tour T-shirt. Each item has a story: a hot-pink alpaca won on a first try at a Japanese arcade a decade ago, or a coffee-stained Matisse print rescued from the roadside with a former roommate.

This trend is resonating deeply with her generation. Spurred by economic instability and the pressures of adulthood, many are finding comfort in tangible connections to their past. ‘Whimsy and nostalgia have been transformed into lifelines,’ Burnard observes, though she questions if this is a healthy embrace of the past or a refusal to let go.

Trinkets as Tangible Timelines

For advocates, these collections are far more than dust-gathering novelties. They are physical diaries, each piece a marker of a person, place, or phase of life. Burnard keeps a ceramic ram that belonged to her grandmother and a collection of Sylvanian Families gifted last Christmas. Even objects that induce ‘unadulterated cringe’—like dusty anime figurines or a framed picture of Lana Del Rey from a ‘stan Twitter’ phase—are cherished for representing who she was.

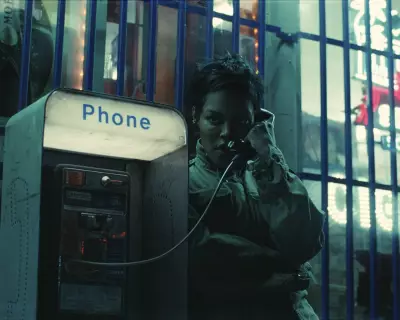

The most poignant items serve as tethers to lost loved ones. Burnard’s mother keeps a small amber glass bird from a friend who died in the 1970s, while Burnard herself treasures a Hello Kitty birthday card from a close friend who was killed the following year. ‘Remembering keeps her alive,’ she writes, highlighting the profound emotional function these objects serve.

Hoarder or Happy Collector?

The line between sentimental curation and problematic hoarding is a fine one, and Burnard acknowledges that others might see her habits as the early signs of a hoarding problem. The labour-intensive dusting and the occasional pang of heartache triggered by an object linked to a lost friendship are the admitted downsides.

Yet, for Burnard and many like her, the benefits outweigh the clutter. In a digital age where memories are often accessed via social media stalks, there is a unique magic in being able to physically touch a piece of one’s history. These trinkets collectively form a mosaic of a life lived, representing ‘all the people we have ever loved’. As minimalism recedes, it seems the desire for a home filled with sweet, saccharine memories is stronger than ever.