A bold government push to build a fresh wave of new towns across the UK is facing significant criticism for failing to prioritise those in greatest need. Senior figures involved in the celebrated post-war new towns programme have warned that current proposals lack the crucial ambition on social housing and risk missing the people who need homes most.

Learning from the Past: The Post-War Blueprint

The criticism draws a direct comparison with the ambitious post-war programme, which created towns like Milton Keynes and East Kilbride. As one letter writer, a former economist for the Milton Keynes Development Corporation, recalls, it was a "close shave" even then. In 1967, with policy swinging towards owner-occupation, a decisive report argued that at least half of Milton Keynes's housing had to be for social rent to achieve its social and industrial mix objectives. This argument ultimately won the day, ensuring the town's success.

Another correspondent, who moved to the new town of Peterborough in 1981, highlights the holistic approach of the era. The Peterborough Development Corporation's master plan didn't just build houses; it created jobs, leisure facilities, safe cycle routes, and self-supporting neighbourhoods with schools and shops, all supported by community workers to help people settle.

The Case for Strengthening Existing Communities

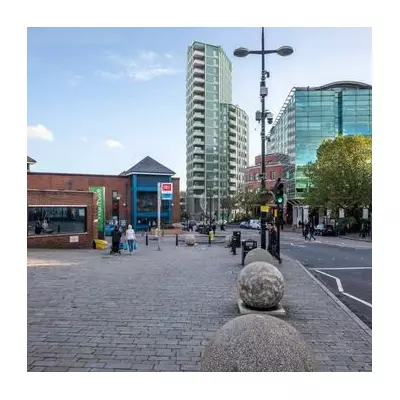

Critics argue that instead of channelling resources into speculative new settlements, the focus should be on the towns and cities already in existence. They point to the enormous potential in redundant land, brownfield sites, vacant upper floors, and derelict retail units across the UK. Developing these areas could deliver affordable, well-located homes more quickly and sustainably, while strengthening rather than displacing established communities.

This approach would also help tackle the parallel crisis on the high street, which is being drained by out-of-town retail parks. Every retailer relocation accelerates decline, reduces footfall, and undermines local economies. Revitalisation, experts contend, requires reinvesting in existing centres where people live, work, and shop.

A Call for Dynamic, Government-Backed Development

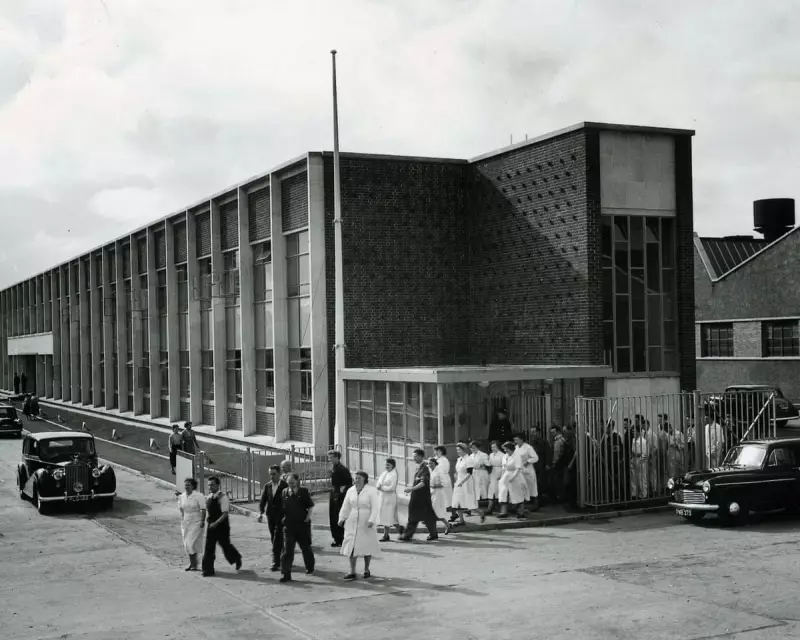

Gordon Davies, a retired architect-planner who worked on new towns including Skelmersdale, East Kilbride, and Livingston, emphasises that true new towns were never just massive housing developments for developer profit. Their success, particularly in Scotland in the 1980s and 1990s, relied on sustained central government support. This enabled the delivery of new jobs in emerging industries like microelectronics, paired with good-quality public housing.

For any future programme to succeed, Davies argues it must be dynamic, providing new employment supported by quality public housing, community facilities, and efficient public transport. Above all, it requires the establishment of powerful new development corporations with the authority to acquire land at existing use value and the planning powers of their predecessors.

The consensus from these expert voices is clear: while new towns may suit developers, they will not alone solve the housing crisis for the most vulnerable. A strategy that repurposes existing urban areas and protects high streets would deliver more homes, more quickly, and with far greater long-term social value.