Australia is embarking on a landmark review of its national code governing the use of animals in scientific research, the first major overhaul in over ten years. The process will confront profound ethical questions, including whether crustaceans should be considered animals and if experiments on primates should be banned.

What the Review Will Examine

The review of the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) code is set to consider several critical updates. A central theme is the formal recognition of animal sentience – the capacity of animals to feel pain and experience emotions. This principle is already enshrined in law in nations like the UK, New Zealand, and across the EU.

Another significant proposal is to expand the legal definition of an "animal" within the code. Currently, it covers mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, and cephalopods. Advocacy groups, including the RSPCA, are pushing for crustaceans like prawns and crabs to be included, arguing that emerging science supports their capacity to suffer.

The review will also evaluate calls for stricter enforcement. Critics highlight that the current system relies heavily on self-regulation by institutions, with limited independent inspections. "Government animal welfare officers only inspect research institutions in response to a cruelty complaint," noted the RSPCA, pointing to a potential conflict of interest.

The Scale of Animal Use in Australian Labs

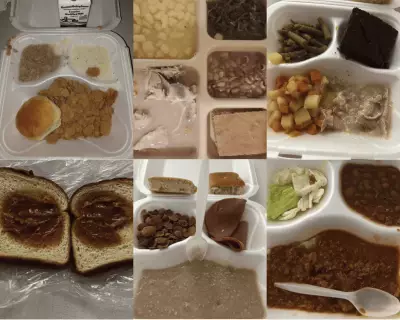

The debate is set against the backdrop of substantial animal use in Australian research. Based on data from Victoria, New South Wales, and Tasmania, more than 845,000 laboratory animals are used each year. This figure includes mice, rats, guinea pigs, rabbits, and primates.

Globally, the scale is even more vast, with an estimated 192 million animals used in research annually. Bella Lear, Chief Executive of Understanding Animal Research Oceania, emphasised that robust, clear policy is needed to "protect animals, and also the people working with those animals." She also advocated for the code to mandate nationwide data collection, as Australia currently lacks consolidated statistics.

Proposed Reforms and Advocacy Positions

Various organisations have submitted strong recommendations for the revised code. Animal Free Science Advocacy is calling for clear prohibitions, including an end to experiments on primates and so-called "high harm" procedures that cause severe or prolonged distress.

The group also seeks to ban the use of animals in teaching, particularly in high schools, and demands that surgical procedures on lab animals be performed only by qualified veterinarians – a standard afforded to domestic pets. "I don't think there should be an exception where a researcher or an animal technician [is] able to perform surgery," said the organisation's chief executive, Rachel Smith.

Furthermore, advocates want a greater onus on researchers to justify why non-animal alternatives cannot be used in their projects. Professor Christine Parker, a specialist in animal welfare law at the University of Melbourne, stated that the code's approach is "out of step with how much Australians care about animals," and that care standards must reflect evolving scientific understanding of sentience.

Next Steps and How to Contribute

The current code, first published in 1969, was last updated in 2013, with a section on cosmetic testing added in 2021. It is adopted under state and territory laws and covers animals used in research, teaching, and environmental studies.

Public feedback on the review is open until 16 February 2025. A revised draft code is expected for further consultation in the second half of 2026. This process represents a pivotal moment for science policy and animal ethics in Australia, balancing research needs with evolving societal values on animal welfare.