A stark new analysis has revealed that adults in England are consuming a dangerous amount of salt each day, equivalent to the quantity found in 22 individual bags of crisps.

The Hidden Salt Crisis in Our Shopping Baskets

Research conducted by the British Heart Foundation (BHF) shows the average daily salt consumption in England has reached 8.4 grams. This is a staggering 40% higher than the official government guideline of a maximum 6 grams per day. Over a week, this adds up to the salt content of 155 bags of ready salted, lightly salted, or sea salt crisps.

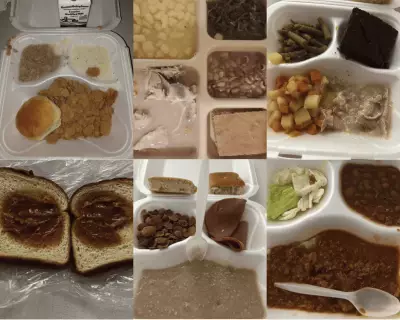

Dell Stanford, a senior dietitian at the BHF, warned that the problem is largely invisible to consumers. "The vast majority of the salt we eat is concealed within everyday products we purchase, like bread, breakfast cereals, pre-made sauces, and ready meals," she explained. "This makes it incredibly difficult for people to monitor or control their intake."

A Major Threat to Heart Health and Lives

This excessive consumption poses a severe risk to public health. Eating too much salt is a leading cause of high blood pressure (hypertension), which is the single biggest trigger for heart attacks and strokes. It is estimated that overly salty diets contribute to at least 5,000 deaths annually in the UK from cardiovascular diseases.

The scale of the issue is further highlighted by hypertension statistics. Around three in ten UK adults are thought to have high blood pressure, yet an estimated 5 million of those are unaware they have the condition, leaving them at unmanaged risk.

Calls for Mandatory Government Intervention

In response to these findings, health campaigners are urging ministers to implement stringent measures to curb salt levels in processed foods. They argue that voluntary measures for the food industry have failed and that legally binding targets are now essential.

"The government must step in to make the healthy choice much easier for families by giving manufacturers an incentive to take out excessive amounts of salt from our food," stated Dell Stanford of the BHF.

Sonia Pombo, head of impact and research at Action on Salt, echoed this call for decisive action. "Salt reduction is one of the simplest, most cost-effective actions any government can take to improve population health," she said. "It requires minimal behaviour change from consumers because the vast majority of salt in our diets comes from the food we buy."

Pombo's recommendations for policymakers include:

- Legally binding salt reduction targets across all food categories with clear deadlines.

- Financial penalties, such as a levy, for products that exceed maximum salt thresholds.

- Compulsory front-of-pack labelling to help shoppers instantly identify high-salt items.

A spokesperson for the Department of Health and Social Care pointed to existing government strategies, stating: "We are taking strong action to tackle health problems caused by poor diet as part of our 10-year health plan. This includes restricting junk food advertising, limiting promotions on less healthy foods high in salt, and introducing mandatory reporting on healthier food sales."

However, health charities insist that without enforceable, sector-wide salt limits, the nation's blood pressure—and the strain on the NHS—will continue to rise unnecessarily.