In a quiet gallery in Manchester, a 54-year-old woman grappling with a life-altering cancer diagnosis found an unexpected source of understanding and comfort in a 19th-century painting. The experience, which she describes as "life looking into a mirror," became a pivotal moment in her journey towards acceptance and recovery.

A Diagnosis That Changed Everything

The discovery of her thyroid cancer was accidental. In May of this year, she underwent an upright MRI scan for a minor arm injury. The imaging, however, incidentally captured a mass in her neck. By the following month, she had received a formal diagnosis. While many reassured her it was "the good cancer"—one with a high survival rate that could be neatly removed—the news was devastating. Being the same age her father was when he died of cancer, the shadow of that history fell heavily upon her.

With her eldest son in the midst of his A-levels, she initially kept the news private. She felt she had crossed an irreversible threshold, a kind of personal Rubicon she had only ever heard happening to others. In the wake of the diagnosis, she retreated from the world, barely leaving her home. Her neck was bruised and swollen, leaving her feeling exposed and vulnerable, as if strangers could see straight through her skin.

A Coaxed Visit and an Unlikely Revelation

It was later that summer when her mother managed to persuade her to leave the house for lunch and a visit to the Whitworth Art Gallery in Manchester. A JMW Turner exhibition was on display. While familiar with the artist's grand seascapes and maritime scenes, she felt disconnected from the "big stuff of someone else's life." She agreed to go purely to please her mother, feeling no desire for culture, fresh air, or any situation where she might be seen.

The exhibition rooms were dark and hushed, lined with sepia-toned prints. As her mother read each caption meticulously, she drifted behind, emotionally numb. While waiting for further test results and consultant meetings, consumed by the fear of whether the cancer had spread, nothing seemed to penetrate her fog of anxiety. She was on the verge of slipping away to the cafe when one particular work brought her to a complete standstill.

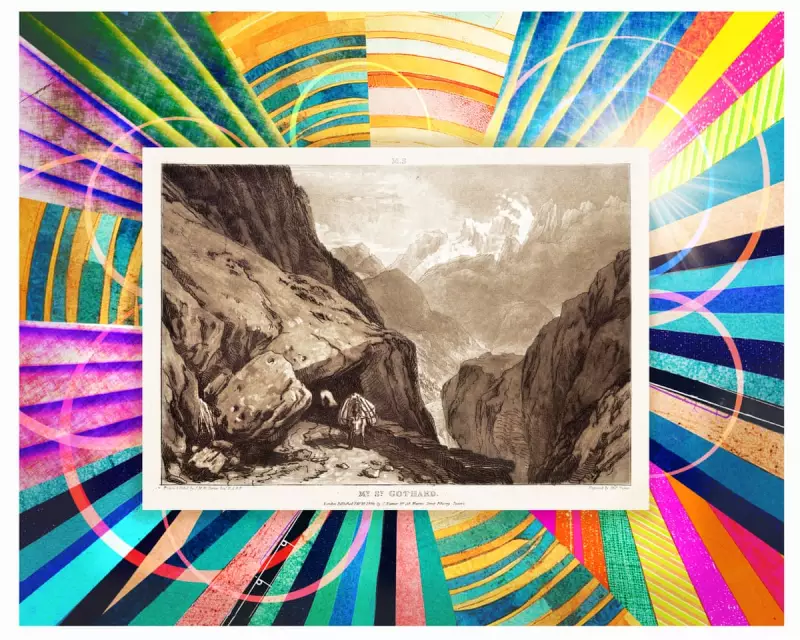

The Mirror in Mount St Gothard

The print was Turner's Mount St Gothard, created in 1808. It depicted a pack horse on a steep mountain path, its head hanging low to the ground, exhausted and pausing under the weight of an impossibly large cargo. In that moment, she saw herself. The overburdened animal, uncertain of how much further the journey stretched, was a perfect reflection of her own physical and emotional state.

"It felt absurd, recognising myself in a horse on a Swiss mountain painted more than 200 years ago," she recalls. Yet, for the first time in weeks, something cut through the mental fog. Her hidden feelings—the fear, vulnerability, and exhaustion she had been managing and downplaying to protect others—suddenly had a shape and a form. This moment of recognition granted her permission to stop solely managing everyone else's expectations and to finally let support in.

The Path to Recovery and Reflection

She notes that today, a 10-mile tunnel cuts through the mountain in the painting, a journey taking just 14 minutes by car. For Turner's horse, the ascent would have taken arduous hours. The parallel was not lost on her. Months later, having undergone two surgeries to fully remove her thyroid and with radioactive iodine treatment ahead as her final medical hurdle, she is starting to feel more like herself.

She has returned to work and is ready to reclaim the creative, joyful parts of life she had set aside. She reflects that the true turning point was not the diagnosis, the operations, or even the relief of knowing her cancer was curable. It was Turner's horse. The animal made it to the top, carrying its burden, and would eventually descend the other side and have its pack removed. "And so will I," she concludes, finding a quiet strength in that centuries-old image of perseverance.