Simon McBurney Remembers Philippe Gaulier: A Clown Who Taught Humanity Through Laughter

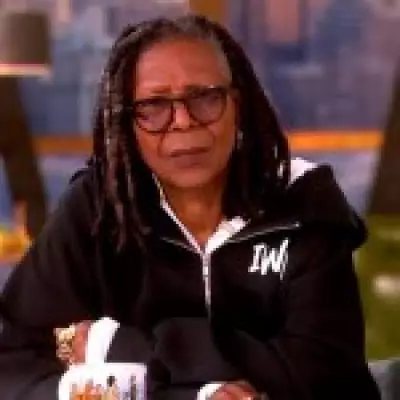

The recent passing of Philippe Gaulier at age 82 has prompted profound reflections from those whose lives he transformed. Simon McBurney, the visionary founder of the groundbreaking theatre company Complicité, shares an intimate portrait of the teacher who reshaped his artistic and personal worldview.

A Life-Changing Encounter in Paris

Many people recall a childhood teacher who fundamentally changed them, someone who revealed essential truths about the world that they carried forward forever. McBurney explains that he never experienced this until age 24, when he stumbled almost accidentally into Gaulier's Paris classroom. "Provocative, demanding, deliberately inappropriate and utterly hilarious, Philippe taught me not to carry anything," McBurney remembers. "No baggage, no ideas; knowing nothing is all you need. Because we are all ridiculous."

The Man Behind the Moustache

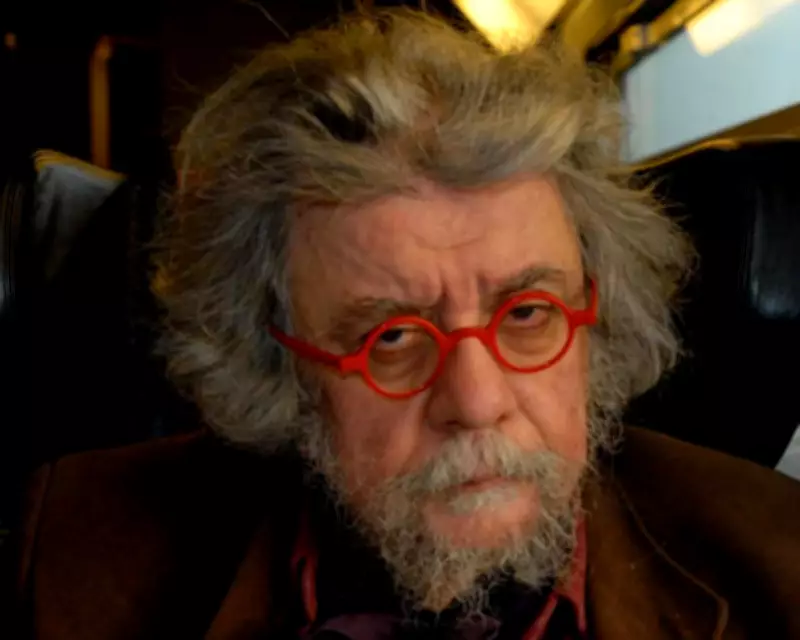

McBurney vividly describes his first encounter with Gaulier on a cold November evening in 1980 at the teacher's Rue Alfred de Vigny studio. The initial impression was unforgettable: a tangled mass of unruly black moustache obscuring the area between nose and lip, a pipe clenched tightly between teeth, wild hair, a bright green sagging sweater, aging boots, and eyes framed by round glasses that "missed nothing, took nothing seriously and ferociously studied every possibility of the hilarious or the pretentious."

The room was filled with people who didn't know what to expect but had heard Gaulier offered something unavailable anywhere else. Their first exchange established the dynamic that would define their relationship. After shaking hands and exchanging greetings, Gaulier looked at McBurney and asked, "You arre eeengleesh?" When McBurney confirmed, Gaulier delivered his first lesson: "Tout le monde a des problèmes" (Everyone has problems), his eyes sparkling with wicked laughter.

Radical Pedagogy and Personal History

Gaulier's teaching method was deliberately structured around power dynamics that students were encouraged to undermine through laughter. "Moi, je suis le professeur, vous ... vous êtes des élèves," he would declare, placing his hand on his belly. The gymnastics teacher became a figure to parody, with power relationships offered as structures to be shattered with humor.

McBurney reveals personal details that shaped Gaulier's worldview. His Spanish mother would cook meals that they ate with relish in his apartment lined with writings, many inscribed with "rêves" (dreams) on the spine. Gaulier referred to his father as "ce salaud bourgeois" (that bourgeois arsehole) and delighted in recounting how he was expelled from school at age eight for punching a gymnastics teacher attempting to instill military-style discipline.

This incident informed Gaulier's lifelong contempt for institutions and attitudes he considered inauthentic. The military, the church, hypocrisy, sham, politicians, academics, and fascists all earned his ire, but "collaborateurs" held special contempt. For someone who grew up in postwar France, this slur was reserved for the most deserving targets, delivered with what McBurney describes as "pleasurable disgust and gastronomic relish" spat from beneath that famous moustache.

The Philosophy of Play and Failure

Gaulier's teaching approach was remarkably individualized. "There was no style, no set ideas," McBurney explains. "Each person was scrupulously attended to, taken apart, built up again, invited, insulted, cajoled, delighted and, most importantly, played with." This play occurred with what McBurney characterizes as "infinite generosity, stomach-aching hilarity, indefatigable persistence and utterly spontaneous flexibility."

Central to Gaulier's philosophy was embracing failure and vulnerability. "We learned to fail, and start again; we learned to jettison our own ideas, because ideas were never the problem, only performing them," McBurney recalls. The teacher believed that when people laugh at you, it reveals a truth, which explains why we typically hate being laughed at in everyday life. With Gaulier, students learned that failing to embrace this vulnerable sense of exposure was "inimical to revealing our humanity."

McBurney emphasizes the radical nature of this approach: "Sharing this fallibility in a complicitous relationship with the audience is a radical act; an anarchic joining to be found in no other art form." This philosophy directly influenced the naming and approach of McBurney's own theatre company, Complicité.

Legacy of a Master Teacher

Gaulier's most famous maxim perhaps best encapsulates his teaching: "If an actor has forgotten what it is like to play as a child, they should not be an actor." McBurney recalls how Gaulier would take him to a bar during lunch breaks after deciding McBurney was his assistant, saying, "Tiens, mon petit, on va chercher de l'inspiration" (Come, my little one, let's go find inspiration), before leaning across the bar with pipe in mouth to order "deux grands martini gins."

Philippe Gaulier's impact extends far beyond theatre, offering what McBurney describes as "a lesson for us all" about embracing the ridiculous to reveal our shared humanity. Through provocative demands, wicked laughter, and infinite generosity, Gaulier taught generations of performers and students that our greatest vulnerability—our ridiculousness—is precisely what makes us human.