Guardian Cartoonists Duel: Capturing Trump Era Chaos in Paint vs Pixels

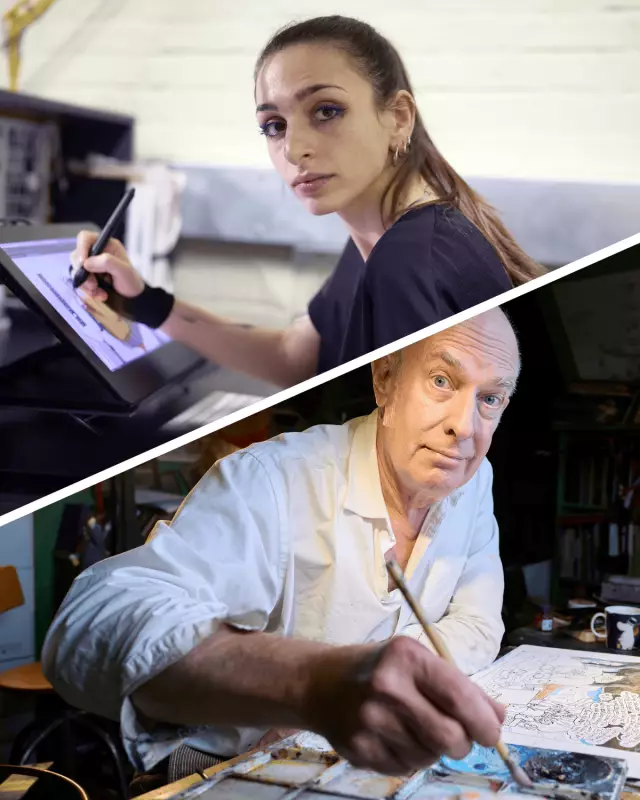

In a fascinating artistic showdown, two of The Guardian's most distinctive political cartoonists have gone head-to-head to capture the turbulent age of Donald Trump and global instability. Martin Rowson, a veteran contributor since the 1980s, and Ella Baron, who joined the newspaper in 2022, were challenged to draw on the same subject on the same day, revealing starkly different approaches through traditional painting and digital creation.

Contrasting Artistic Philosophies and Techniques

The experiment highlighted how each cartoonist interprets political chaos through their unique lens. Rowson, describing himself as "old school," works exclusively with physical materials—pencils, pens, brushes, gouache, and watercolour on paper. He embraces the tactile experience and inherent uncertainty of traditional media, citing influences from satirical giants like James Gillray and William Hogarth. His process involves listening to morning news headlines and rapidly colliding images in his mind before translating them onto paper through layered painting techniques.

Baron, representing the digital generation, creates exclusively using a Wacom Cintiq tablet and stylus. She argues passionately that digital drawing "is drawing by hand," with her tools offering precision that allows for minute adjustments impossible with physical media. Growing up with digital technology as her native artistic language, she focuses on refining lines and expressions to capture subtle power dynamics in political figures.

The Trump Challenge: Shakespearean Kings and Dystopian Nests

For their simultaneous Trump-themed cartoons, Rowson produced a warped Shakespearean scene featuring "King Leer" surrounded by snickering world leaders, while Baron depicted the former president squatting in a dystopian nest surrounded by spoils. Both artists reflected on how Trump's evolving public persona has influenced their caricatures, with Rowson noting his subject has become "older, flappier, fleshier and madder" over the decade, while Baron focuses on undermining his projected image through revealing details like uneven tan lines and visible bald patches.

The Creative Process: From Morning Headlines to Finished Art

Rowson's day begins with BBC Radio 3's 7am news, after which he develops a complete mental image within twenty minutes. He then spends approximately six hours transforming this vision onto paper through sketching, inking, and painting. The physical scale of his work—drawn 50% larger than the printed version—allows for intricate detail and flexibility as news stories develop throughout the day.

Baron's digital process involves "surfing through the news" for symbolic imagery, which she mentally shuffles "like a deck of cards" until forming a coherent composition. She values the tight deadlines that force distillation of complex ideas into essential visual elements, arguing that cartoons "can't encapsulate the news, but can cut through it" by offering hypothetical twists on reality.

Mutual Admiration and Evolving Traditions

Despite their methodological differences, both cartoonists express deep respect for each other's work. Rowson admits Baron's digital process remains "a total mystery" to him while acknowledging her as part of the medium's future. Baron reveals she has admired Rowson's work "all my life" and that his caricatures have fundamentally shaped how she perceives and draws politicians.

The cartoonists also reflect on their place within the long tradition of political satire. Rowson sees continuity in content despite technological changes, noting that "visual satire has been around for as long as we've had elites that require satirising." Baron describes working "slightly in awe" of this tradition while navigating her unique position as a female cartoonist in a historically male-dominated field, gradually reclaiming feminine elements in her style and concepts.

The Enduring Power of Political Cartoons

Both artists agree on the continued relevance of political cartoons in turbulent times. Rowson believes they serve to "enrage his cultists but comfort and empower the rest of us," while Baron sees them as vital tools for holding power to account by placing powerful figures in close proximity with those affected by their decisions on the page.

Their contrasting approaches—Rowson's embrace of physical messiness and Baron's digital precision—demonstrate how political satire continues to evolve while maintaining its essential function: to critique, challenge, and illuminate through visual storytelling in an increasingly chaotic political landscape.