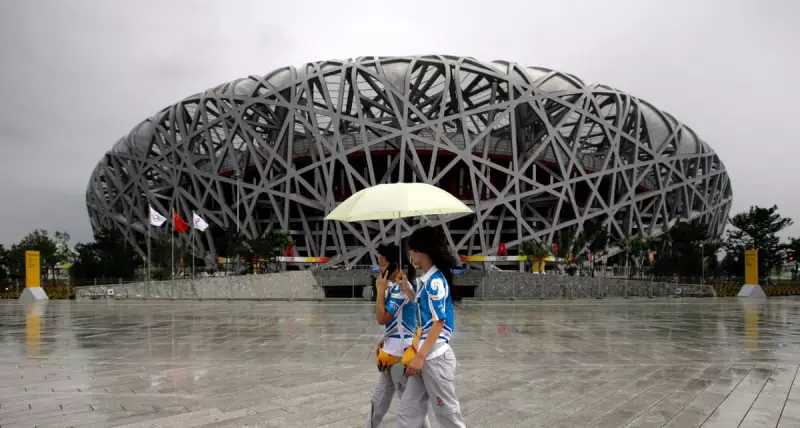

When the Taiwanese rock band Mayday prepared for a concert at Beijing's National Stadium in May 2023, fans fretted about forecast rain. Little did they know, the iconic venue, nicknamed the Bird's Nest, was uniquely equipped for downpours. Its secret lies in a sophisticated system that captures and reuses rainwater, embodying a nationwide push to blend ancient wisdom with modern ecological design.

The Bird's Nest's Secret Weapon

Built for the 2008 Olympics, the stadium's intricate steel lattice is more than an architectural marvel. Woven through its structure is a network of capillary-like pipes designed to siphon rainfall away. This water is channelled into three underwater storage tanks, where it is filtered and prepared for reuse within the building.

The Chinese ministry of water resources states this system can meet over 50% of the stadium's water needs, from flushing toilets to washing the running tracks and watering surrounding lawns. In total, the infrastructure around the Bird's Nest can treat a staggering 58,000 tonnes of rainwater annually.

From Ancient Courtyards to Modern Sponge Cities

This practice, known as Urban Rainwater Harvesting (URWH), is not confined to the Bird's Nest. Across the road, the National Aquatics Centre collects roughly 10,000 tonnes of rainwater a year. According to Beijing authorities, the city now reuses 50 million cubic metres of rainwater each year, with recycled sources meeting more than 30% of its water demands.

The movement is deeply rooted in history. Wang Dong, director general at the ecological city studio Turenscape, explains that traditional Chinese homes were designed with courtyards where rooftops collected water, symbolising wealth being kept within the family. This ancient affinity for water management has been revived through the modern "sponge city" concept, pioneered by landscape architect Yu Kongjian.

Officially adopted by the Chinese government in 2014, the sponge city strategy uses green spaces, wetlands, and permeable surfaces to absorb rainfall, mitigate flooding, and crucially, capture water for reuse. The national target is for 70% of rainfall in these cities to be harvested and reused.

A Flourishing Industry and Architectural Imperative

The trend extends beyond public infrastructure. In 2022, drone giant DJI unveiled its Shenzhen headquarters, featuring sky gardens and an integrated rainwater system for irrigation. The URWH industry in China, encompassing tanks and filtration systems, was valued at 126 billion yuan (£13.5bn) in 2023 and continues to grow.

For architects working in China, incorporating such systems is now fundamental. Dan Sibert, a senior partner at Foster and Partners, who worked on the DJI project, emphasises that effective rainwater design is "absolutely fundamental to the development, not a sort of add-on that comes a bit later on."

The challenge involves creating parallel "grey" water systems to keep recycled water separate from drinking supplies. Yet, as Sibert notes, it enhances the user experience: "If you’re flushing the toilet using grey water, it’s good that people know that." It transforms a potential constraint into a feature that makes buildings both ecologically friendly and resilient, addressing water scarcity challenges that have persisted for millennia.