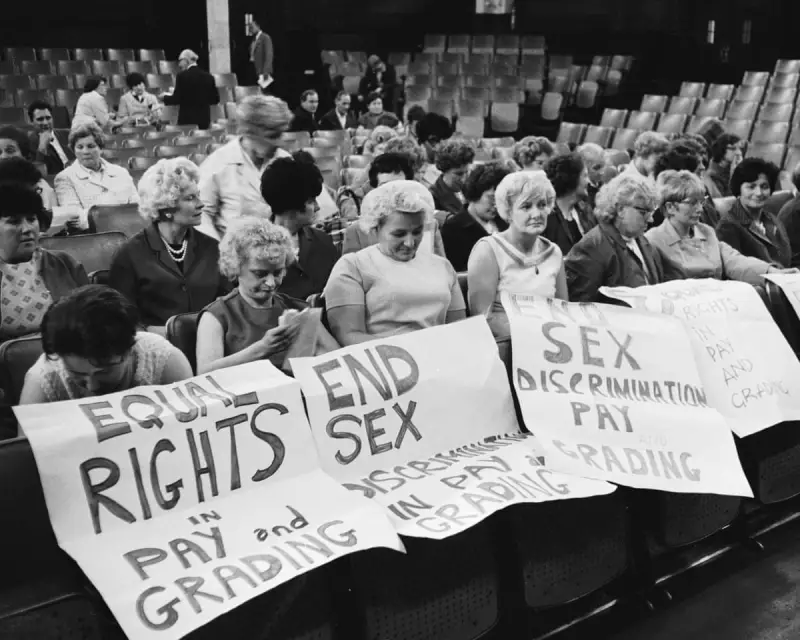

In June 1968, a pivotal moment in British industrial and feminist history unfolded not on a picket line, but at a conference in Euston. 187 female sewing machinists from Ford's Dagenham plant, then on strike, attended a women's conference on equal rights at Friends House. While their action is often hailed as a landmark for equal pay, the core grievance was more nuanced: a demand for their work to be recognised as skilled.

The Spark: A Demeaning Grade

The strike was triggered by the Ford Motor Company's introduction of a new grading structure in 1967. The company evaluated the complex work of the machinists, who stitched car seat covers, as grade B, classified as 'unskilled'. The women were outraged, firmly believing their intricate and precise work constituted at least semi-skilled labour, which should have been graded C. This was not initially a simple demand to be paid the same as men; it was a fight for the company and the union to acknowledge the inherent skill and value of their specific job.

Castle's Intervention and a Temporary Fix

The strike was effective, bringing Ford's production lines to a halt. The government, led by Secretary of State for Employment and Productivity Barbara Castle, intervened to negotiate. The settlement reached saw the women return to work after being offered a pay rise that would bring their wages from 85% to 100% of the male grade B rate over two years. While this addressed a pay disparity, it did not resolve the fundamental issue of the grading. Their work was still officially classified as unskilled.

The Long Road to Final Victory

The true resolution of the machinists' grievance took another 16 years and a further strike in 1984. This time, the women utilised the new Equal Value (Amendment) Regulations of 1983. A panel from the Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (Acas) was convened to independently evaluate their job. The panel's decision was unanimous: the sewing machinists' work was indeed skilled. They were finally regraded to grade C, winning the long-fought battle for professional recognition.

This protracted struggle underscores a critical distinction in labour history. The Dagenham sewing machinists' primary fight was for the acknowledgement of their skill and the value of their work. Their legendary strike, while catalysing the equal pay debate, was fundamentally about dignity, professional respect, and correcting a discriminatory assessment that undervalued a predominantly female workforce. Their ultimate victory in 1984 set a crucial legal and industrial precedent for evaluating work based on its true worth.