A prominent Syrian winery that once produced 50,000 bottles annually is staring at financial ruin, unable to sell a single drop for over a year due to legal ambiguity under the country's new Islamist-led government.

From Regime Souvenirs to Rebel Memorabilia

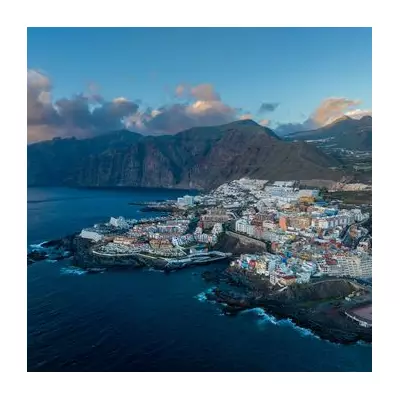

The cultural transformation sweeping Syria is vividly illustrated in places like Abu Ali's tourist shop in the coastal city of Tartous. In the immediate aftermath of President Bashar al-Assad's fall, the 48-year-old shopkeeper packed away his old stock of regime-themed merchandise.

Today, his shelves hold a different narrative: the new three-star Syrian flag, jewellery boxes engraved with revolutionary slogans, and pictures of fallen rebel fighters. "Business is slow these days," Ali admits, noting the disappearance of his former clientele of Russian soldiers, Western war tourists, and Lebanese visitors.

Vineyards in a State of Flux

For Syria's ancient vineyards, the political upheaval has created profound uncertainty. Shadi Jarjour, owner of the Jarjour winery in the hills above Tartous, describes a paradoxical situation. While the end of the Assad dynasty halted the "ceaseless harassment" from corrupt officials, it ushered in a new era of limbo for his business.

The winery, which had been expanding its production and cultivating a more sophisticated local wine culture, can still technically produce wine. However, the absence of clear legislation governing alcohol sales under the new administration has frozen its commercial operations since December 2024.

"I haven't sold anything since December 2024. If a law isn't published in the next month or so, I will have almost two years of losses," Jarjour stated, highlighting the dire financial impact.

A Capital Navigating New Rules

This legal grey area is felt nationwide. In Damascus, authorities have conducted raids on bars, closing them under the pretext of licensing issues, despite no clear process to obtain or renew such licences. After public outcry, most bars reopened, but the threat of arbitrary enforcement remains.

One bar owner recounted being forced to close temporarily, with an official later stating it was a "little lesson" for operating during Ramadan—an action not prohibited by any formal law. Despite this, a vibrant, underground party scene persists in the capital, a testament to the complex negotiation between new authorities and old social habits.

Syrians are cautiously navigating this new landscape, testing the boundaries of expression after decades of autocracy. The government, whose core includes former members of the Islamist rebel group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), has sent mixed signals, privately assuring businesses like Jarjour's of non-interference while publicly failing to legislate.

Despite the challenges, Shadi Jarjour remains hopeful. He dreams of expanding his winery's domestic market and eventually exporting, building a global brand for Syria. "We are waiting to see what the new laws will be, and we hope it comes soon so we can get back to work," he said, echoing the sentiment of many Syrian businesses caught in the nation's protracted cultural flux.