London is a city in a state of perpetual motion, its skyline and streetscape evolving at a breathtaking pace. For anyone who last visited the capital five decades ago, the modern metropolis would be almost entirely unrecognisable. The relentless march of development has seen entire districts rise from derelict docklands, historic areas rebuilt from wartime ashes, and a forest of skyscrapers pierce the clouds where low-rise buildings once stood.

From Blitzed Ruins to Concrete Icons

The scars of the Second World War fundamentally reshaped parts of London, creating blank canvases for ambitious post-war visions. The City of London, the historic Square Mile established by the Romans in 47AD, suffered devastating damage during the Blitz. While St Paul's Cathedral famously survived, the particularly heavy raids of late December 1940 caused a firestorm dubbed the Second Great Fire of London, obliterating huge swathes of the area.

This destruction paved the way for a dramatic rebuilding programme. The decades following the war saw reconstruction, but it was the 1970s that witnessed the UK's first true skyscraper: the 600-foot, 47-storey NatWest Tower. This set a precedent, leading to the iconic cluster of 21st-century towers we see today, including the Gherkin, the Cheesegrater, and the Walkie-Talkie.

Similarly, the Barbican area was virtually flattened during the war. The Cripplegate ward was demolished, and by 1951, the resident population of the City had plummeted to just 5,324. The decision to build a new residential estate was taken in 1957. The resulting Barbican Estate, built between 1965 and 1976 on a 35-acre site, was designed by architects Chamberlin, Powell and Bon not as social housing, but as luxury accommodation for affluent City professionals, attracting judges, bankers, and politicians.

Docklands to Financial Powerhouse

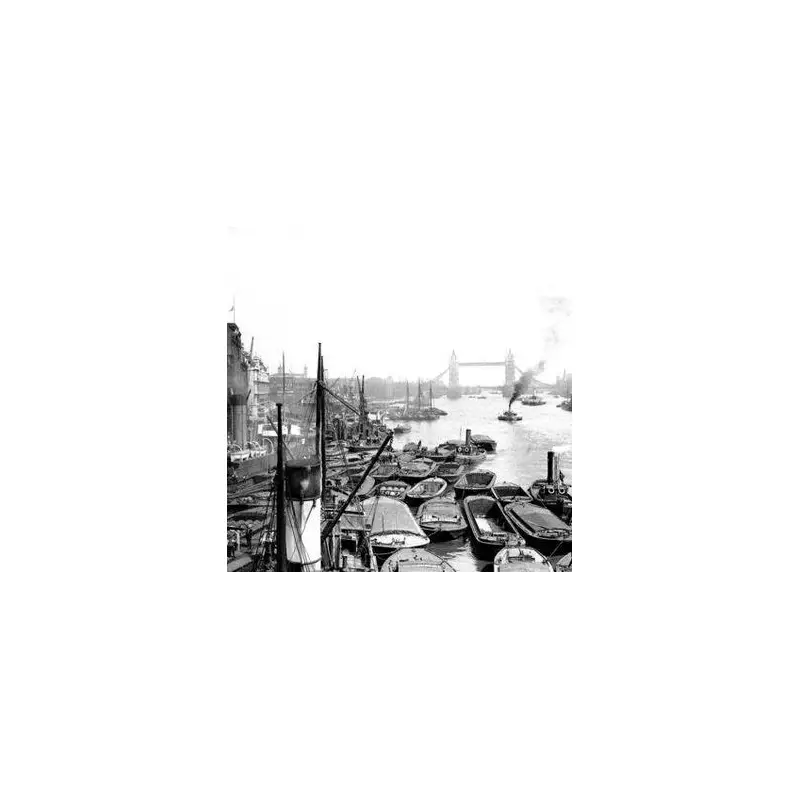

Perhaps the most striking metamorphosis occurred in East London. The area now known as Canary Wharf was, for much of the 20th century, a bustling part of the West India Docks. However, the containerisation of cargo in the 1960s led to a steep decline, and all docks were closed by 1980.

The British Government's intervention, including creating the London Docklands Development Corporation in 1981, sparked regeneration. The vision for a new business district took hold, master-planned by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. Construction began in 1988, and the first buildings, including One Canada Square, were completed in 1991, symbolising the rebirth of the Docklands as a global financial centre.

Industrial Giants Reborn

Other transformations have seen industrial landmarks repurposed for a new age. Battersea Power Station, one of the world's largest brick buildings, was decommissioned in stages, with the final section closing in 1983. After decades of uncertainty, a 2012 agreement with Malaysian developers set in motion a vast project to convert the Grade II* listed structure. The main building reopened to the public in October 2022, now housing shops, restaurants, offices, and apartments.

Even London's most famous streets are not immune to change. Oxford Street, Europe's busiest shopping street, is on the cusp of its biggest shift in a century. In late 2025, Mayor Sadiq Khan announced plans to permanently pedestrianise a 1.1km stretch, banning most vehicles and rerouting buses to create a major new public space, with consultations ongoing into 2026.

From the realignment of tube lines for the Barbican to the construction of the Docklands Light Railway for Canary Wharf, transport links have consistently altered the city's flow and form. These eight locations—the City, Barbican, Canary Wharf, Battersea, Tower Bridge, Piccadilly Circus, and Oxford Street—stand as powerful testament to a capital that is constantly rewriting its own architectural and social narrative, ensuring the London of tomorrow will always look different from the London of today.