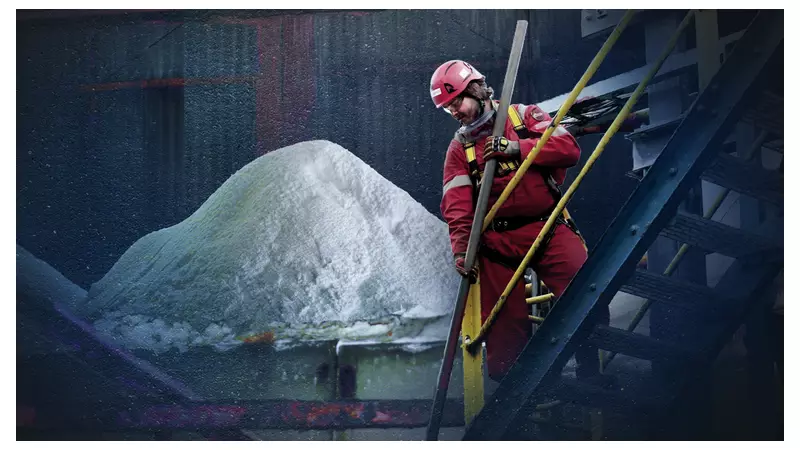

The UK stands on the brink of losing its centuries-old self-sufficiency in salt, a move that would symbolise the final decline of a chemical industry that was once the pride of the nation. Sky News can reveal that Inovyn, which produces half of Britain's salt, may be forced to close its Runcorn plant without government support, making the country reliant on imports for the first time in its modern history.

The Bedrock of Industry Under Threat

For hundreds of years, Britain has produced all the salt it needs from a vast underground deposit of rock salt in Cheshire. This humble substance is far more than a seasoning; it is the bedrock of the chemical sector. Derivatives of salt are found in 90% of all pharmaceuticals and are essential for water purification, plastics, explosives, and countless other materials. The UK currently produces nearly 3 million tonnes annually, processed at two main plants run by Tata Chemicals Europe and Inovyn.

Tom Crotty, group director of chemicals at INEOS, which owns Inovyn, warned of the consequences of closure. "Without a plant like this, we'd have to import," he said. "Salt is corrosive and low-value, so transport costs dramatically inflate the price. This would make UK industries, like food production, uncompetitive."

A Wider Crisis in Foundational Chemicals

The potential end of British salt production is just one symptom of a far deeper crisis. Sky News research has identified 11 major chemical plant closures in the last decade, many producing foundational chemicals critical to other sectors. This collapse is unprecedented outside of world wars, with sector output falling by 20% in just three years.

The UK has already lost the ability to make several core industrial building blocks:

- Ammonia: Vital for nitrogen-based fertilisers, its production ceased in 2023 with the closure of the CF Fertilisers plant in Billingham.

- Sulphuric and Nitric Acid: Inovyn shut its sulphuric acid plant in Runcorn, a key ingredient for explosives and other products.

- Soda Ash (Sodium Carbonate): Tata closed its Lostock plant last year, ending 150 years of UK production of this chemical essential for glass and paper.

Sharon Todd, head of the SCI charity, stated: "We've probably lost 90% of the core building blocks that we need."

Energy Costs and Aged Infrastructure

The primary driver of this decline is the UK's high industrial energy prices, which make energy-intensive chemical production unviable compared to countries like the US and China. Compounding this is an ageing infrastructure base, much of it dating back to the era of ICI, the collapsed British chemical giant.

A visit to the vast Wilton site on Teesside, once the heart of the UK's petrochemical industry, reveals the stark reality. Peter Huntsman, CEO of Huntsman International, which runs one of the last remaining plants there, called the scene "terribly depressing."

"The raw materials are still here, the workers are still here... You could have this industry back if the government wanted," he said. "Nobody sees the raw materials... but these are the essential building blocks of modern society. Without it, you're just a service economy."

While the government offered a grant in December to save the INEOS ethylene cracker at Grangemouth, the industry views this as a sticking plaster. The broader crisis, fuelled by energy costs and carbon taxes, remains unaddressed. The continued closure of carbon-intensive plants does, however, edge the UK closer to its 2050 net zero target—a trade-off that highlights the complex challenge of balancing industrial strategy with environmental goals.